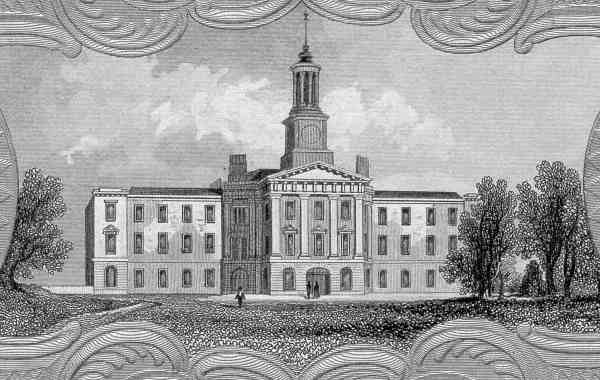

House of Refuge for Boys, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland

Efforts to establish a boys' reformatory institution in Glasgow date from 1801 when a Professor of Divinity named Stevenson MacGill founded the Glasgow Society for the Encouragement of Penitents. The Society aimed to rescue and reform juvenile offenders by establish two charitable institutions: a 'halfway house' for boys convicted of vagrancy, and a home for young prostitutes, or 'magdalenes'. As a result of their efforts, the city's Magdalene Asylum was opened in 1816, funded by private contributions. Support for the male establishment was less forthcoming, however, and the Society's work amongst boys was eventually abandoned.

A further attempt to establish a boys' reformatory was launched in 1826 by William Brebner, governor of the city's Bridewell Prison. Brebner argued that the short sentences which were then being handed out to many young offenders were having little effect on the street gangs which then plagued the streets. While in the Bridewell, first-time offenders mixed with hardened criminals and soon gained bad habits. He proposed that a separate reformatory institution be established for first-time offenders, where education and vocational training would be provided. Finally, by 1837, Brebner — working with the chief of the Glasgow Police Office — had managed to raise pledges of £10,000 for the construction of a Boys' House of Refuge. The building, designed by John Bryce, was erected at Annfield Place, 325 Duke Street, Glasgow, and began operation on 18 February 1838, with accommodation for up to 300 inmates. It quickly proved successful reducing crime in the city that a large part of the Magdalene Asylum was turned over for use as a girls' reformatory, and renamed the House of Refuge for Females.

On 15 November 1854 the Boys House of Refuge was certified to operate as a Reformatory under the Reformatory Act of that year which laid the foundation for a national system of reformatory establishments. The Duke Street premises were licensed to accommodate up to 440 boys, aged from 10 to 15 years at their date of admission. The Reformatory was the largest such institution in Britain.

The House of Refuge site is shown on the 1857 map below.

House of Refuge for Boys site, Glasgow, c.1857.

House of Refuge for Boys, Glasgow.

An inspection in 1857 noted the boys' industrial occupations included tailoring, shoemaking, printing, book-binding, carpentering, smith's work, coopering, wood-cutting and gardening, the latter being carried out on some land two miles away. The staff consisted of the chaplain-superintendent, the Rev. A, McCallum; five schoolmasters, labour masters in the trade department, cook, porter, clerk etc. The following year, a new school-room was added, divided into three sections so as to allow three classes of 60 or 70 boys to be instructed separately at the same time. Simple military exercises and drill were regularly carried out. Regular rewards were given for good work or conduct and occasional small gratuities were given to the more industrious boys. A farm school was in the course of being established to provide the boys with field training. Active exercise and amusements such as football were encouraged.

On Tuesday 27 March 1860, a fatal accident occurred when at about one o'clock in the morning, four boys, named William Taylor, James Cairney, Alexander Dunsmore, and William Neil, made an attempt to escape from their top-floor dormitory. They piled up benches, bedding, etc., to reach a ventilator in the roof, through which to make their exit. Having previously formed a makeshift rope from all the blankets, mats and towels they could in the dormitory, the first three succeeded in letting themselves down from the roof. William Neil, however, met his death when the rope gave way when he was about 50 feet from the ground. So severe were his injuries that he expired at eight o'clock the same morning. The discovery of the events was due to one of the young inmates who slept in close proximity to the runaways. After hearing an unusual noise, and suspecting its cause, he opened his window and shouted 'Boys escaping.' A watchman in the neighbourhood heard the cries and on proceeding to the spot, he found the boy who had met with the accident. The other boys three succeeded in making their escape.

A report of the above events in the following day's Glasgow Herald commented, 'We suspect the discipline of this place requires to be managed according to a sterner code than that now practised, for, if we are not misinformed, one of the boys, about three weeks ago, stabbed one of his masters very severely.' On 4 April, the Herald published a letter signed 'A Friend of the Cause' making a number of allegations about the management of the establishment. The writer suggested that very bad discipline must prevail at the institution, as the escape had itself indicated. When a mysterious fire had recently occurred in one the attics, they boys had refused to help put it out but had 'cheered lustily'. There was in fact 'a horrid threefold combination — incendiarism, conspiracy, and mutiny.' The author suggested that such a large establishment would be better carried on under the family group system as practised at model institutions such as Mettray in France and Redhill in Surrey, rather than the associative system which was used at Glasgow. A second letter, signed 'An Inmate', appeared in the paper on 12 April. Stating that a master had been stabbed by one of the boys at the Reformatory on 26 February, 'but not without cause'. The same boy was said to have received 50 lashes and for the following week had been fed on just 3 ounces of biscuit a day. One of the other boys who had been involved in the escape on 27 March was described as 'lying in the lock-up, with one of his legs all shattered, and his body bruised' after being severely punished. Boys who raised complaints were alleged to be 'kicked about like dogs' and receive 30 or 40 lashes with a pair of taws, 8½ pounds in weight. The food was said to be 'not fit for pigs' and cockroaches were often found in the porridge.

An internal committee appointed to examine the claims made in the Herald published its findings in mid-May. The report essentially rebutted all the allegations. The recent fire was said to be accidental, although it was true that some of the younger boys had raised a cheer when the fire engines had arrived to deal with it. The so-called stabbing had been a thrust with a pocket knife under the momentary influence of passion. for which the boy concerned had since repeatedly expressed regret. The punishment administered had not been more than 25 lashes and with a six-ounce taws, the only one in use at the school. Boys were never fed exclusively on bread and water. The boy who was injured in the escape attempt had confirmed that he had not been punished following the event and had been kindly treated an properly taken care of. Cockroaches were known to get into the porridge but this was a very rare occurrence. The committee had also had certain complaints by the assistant teachers brought before them and changes were being contemplated to deal with these.

The Reformatory's inspection report for 1860 suggested that the religious and educational influence by which the reformatory had been brought to a high a state of efficiency and usefulness had been replaced by mechanical discipline. This had given an outward appearance of order, but in reality had reduces the school to a machine, characterised by hasty and improper punishments being administered by the assistant officers, leading to resistance, violence, and desertion among the boys. It was noted that since the investigation, a large number of the older boys have been discharged; the schoolmasters had been brought into more contact with the boys, and enabled to have more influence over them; strict regulations had been laid down as to punishments, restricting the inferior officers from inflicting them; and many improvements had been carried out in the arrangements of the premises, and a housekeeper engaged to take charge of the kitchen and the infirmary. It was also recommended that the number of boys be reduced to something like 200.

The following year's inspection gave a much better account of the school. A halt had been made to all irregular punishments by subordinate officers, the general discipline had become more kindly, and the school teachers were engaged among the boys during the evening. In addition, considerable progress had been made in the establishment of the branch Farm School at Riddrie (or Reddrie), for the employment and training of some of the boys in agricultural work. The Riddrie site was formally certified for operation on 16 January 1867.

At the end of 1866, an official inquiry was launched after an officer of the institution, recently dismissed by Mr McCallum, had made a complaint to the Home Office. The inquiry found that 'immoral and indecent practices had prevailed long and largely among the boys, especially the oldest and more trusted ones'. The existence of these activities had been ignored by Mr McCallum and the officers in whom he placed most confidence. After Mr McCallum's subsequent resignation, all admissions were suspended while the internal discipline and arrangements were revised. The number of places at the school during the year was reduced to 150. The school's small dormitories were converted into large ones, and the iron grates shutting off the passages to the dormitories and the iron bars to the windows were removed. These alterations were intended to give more of the character of a school to the institution, and to take away much of its prison aspect. The head schoolmaster, Mr John Rae, was appointed as interim superintendent. In September 1867 he was succeeded by Mr David Allan, previously superintendent of the Kibble Reformatory at Paisley. Mrs Allan was appointed matron. Mr Rae then replaced Mr Allan at Paisley.

Despite the high hope that were held for the Riddrie Farm, the site was given up in 1871 owing to the expense it entailed, its distance from the main school, and relatively small numbers of boys trained there.

In the early part of 1878, Mr Allan was taken seriously ill. He was obliged to retire from his post and died on 7th April. During his initial absence, considerable insubordination ensued. Following his death, an open revolt and rebellion took place, resulting in much violence and disturbance, requiring the intervention of the police to restore order. Thirteen boys were sent to prison for a term and some of the ringleaders were transferred to other Reformatories. Mr John Rae was subsequently appointed superintendent.

Since the reduction in the number of boys at the school, the premises were increasingly found to be too large and unwieldy. In 1880, the directors began to contemplate erecting a new and more suitable building a little further from the city, if a suitable site could be found. The staff now comprised: superintendent and matron, Mr and Mrs John Rae; clerk, Mr McDonald; teacher, Mr McArthur; assistants, Mr Gilfillan and Mr. McFadyen; two shoemakers, two tailors, two coopers, joiner, baker, cook, night watchman, van driver, engineer and smith, two gardeners, three shoe machinists, sick-nurse, general servant, bandmaster and drill instructor, and medical officer.

More disciplinary problems occurred in September 1881, and again in January and February 1882, when there was much riotous and mutinous behaviour. In January many of the boys armed themselves with shoemakers' knives and pieces of iron, and several of the boys attacked the governor. The police had to be called in; six boys absconded, but were brought back. On the 4 February there were preparations and plans for another outbreak and 12 boys were punished. There had been a good deal of insolent and insubordinate conduct at other times during the year, mainly in the shoemakers' shop. There were now 12 boys occupied in the carpenters' shop. Boys who had only left the school six months were earning from 10 to 30 shillings a week; as a rule the carpenters followed their trade on discharge. There were 10 boys employed in the bakehouse, where about 7 or 8 tons of biscuits were made and sold annually. About 22 boys were employed in making small barrels or firkins, who if they continued at the same work on discharge could earn from 10 to 15 shillings a week to start with. There were 15 boys in the tailors' shop and 45 in the shoemakers'. Five boys worked in the garden.

In 1883, it was reported that the site and buildings had been disposed of, with the school remaining in residence until it had obtained new premises.

The 1885 inspection recorded only 85 boys at the school and only a small part of the buildings were in use. In March there was some trouble when 13 boys absconded after procuring a ladder from one of the workshops; they were soon brought back to the school, however. There had been five other cases of absconding during the year, and two boys were still absent. A mark system had been established, the marks having a money value by which a boy could earn ld. a week. In addition to this payments were made for good work done in the workshops.

In 1886, the directors of the school decided that it should be closed down. This took place at the end of April 1887. The boys then under detention were disposed of, some to their friends, some on licence to employment, and a certain number emigrated o Canada.

After the school's closure, the premises were demolished and the East End Exhibition buildings were built in their place. The modern housing of Whitehill Court now occupies the site.

From 1873 to 1875, the Riddrie Farm site was occupied by the Glasgow Boys Industrial School after a fire destroyed most of their premises at Mossbank. Riddrie was also occupied between 1879 and 1882 by the House of Refuge for Females while their new premises at Chapelton were under construction.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Glasgow City Archives, The Mitchell Library, 210 North Street, Glasgow G3 7DN, Scotland.

Census

Bibliography

- Carpenter, Mary Reformatory Schools, for the Children of the Perishing and Dangerous Classes, and for Juvenile Offenders (1851, General Books; various reprints available)

- Carlebach, Julius Caring for Children in Trouble (1970, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Higginbotham, Peter Children's Homes: A History of Institutional Care for Britain's Young (2017, Pen & Sword)

- Abel Smith, Doroth Crouchfield: A History of the Herts Training School 1857-1982 (2008, Able Publishing)

- Garnett, Emmeline Juvenile offenders in Victorian Lancashire: W J Garnnett and the Bleasdale Reformatory (2008, Regional Heritage Centre, Lancaster University)

- Hicks, J.D. The Yorkshire Catholic Reformatory, Market Weighton (1996, East Yorkshire Local History Society)

- Slocombe, Ivor Wiltshire Reformatory for Boys, Warminster, 1856-1924 (2005, Hobnob Press)

- Duckworth, J.S. The Hardwicke Reformatory School, Gloucestershire (in Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1995, Vol. 113, 151-165)

Links

- Red Lodge Museum, Bristol — a former girls' reformatory.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.