'Our First Arab' by Thomas Barnardo

Thomas Barnardo's first encounter with the destitute boy, Jim Jarvis (or Jervis), at the Hope Place ragged school in Limehouse made a deep impression on him. Over the years, Barnardo retold the story of the meeting many times, often with some variation in the detail. Below is one of the longer versions.

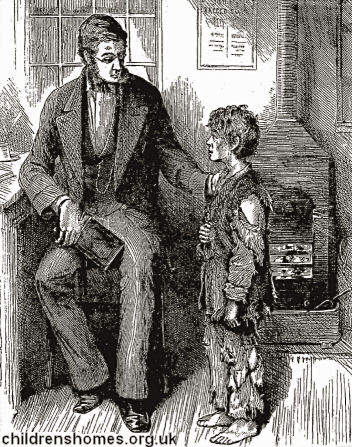

Thomas Barnardo and Jim Jarvis.

One evening, the attendants at the ragged-school had met as usual, and at about half-past nine o'clock were separating for their homes. A little lad, whom we had noticed listening very attentively during the evening, was amongst the last to leave, and his steps were slow and unwilling.

'Come, my lad, it's time to go home now.'

To this no reply was at first given.

'Come, I say, you had better go home at once.' Then I added somewhat doubtfully: 'If you don't, your mother will be asking for you.'

'Please, sir,' slowly drawled the lad, 'let me stop.'

'Stop!' said I; what for? Indeed I cannot. I am going to turn the lights out and lock the door. It's quite time for a little boy like you to go home and get to bed. What do you want to stop for?'

'Please, sir,' he repeated, 'do let me atop; I won't do no 'arm.'

'I cannot let you stop, my boy. Why do you want to stop for?' You ought to go home at once. Your mother will know the other boys have gone, and will wonder what keeps you so late.'

'I ain't got no mother.'

'But — your father? Where is he?'

'I ain't got no father.'

'Stuff and nonsense, my boy!' I said, somewhat brusquely, Don't tell me such stories! You say you have not got either a father or a mother. Where are your friends, then? Where do you live?'

'Ain't got no friends. Don't live nowhere!'

I was startled, as I have said, by such a reply. But I did not believe it, although I could not help feeling that there was something behind it which needed inquiring into. So I called the boy to me in the words with which this little story opened.

It was with slow and heavy steps that the boy came nearer He moved each foot as though it were weighted, and some seconds elapsed before he was close enough to let me look at him narrowly. But at last he stood directly in front of me either a lying young scamp who deserved a good whipping, or one of the saddest little urchins I had ever seen. Which was it?

I looked searchingly at the child — for he was little more than a child — and to this hour, as I close my eyes, the face and figure of the boy stand out sharp and clear before my mental vision. He had a small, spare, stunted frame, and he was clad in miserable rags — loathsome from their dirt — without either shirt, shoes, or stockings. Sure enough I could see that here was a phase of poverty far beneath anything with which the noisy, wayward children of my ragged school had familiarised me.

'How old are you, my boy?' I said at last.

'Ten, sir,' he replied slowly. He looked older; but his poor little body seemed fitter for a boy of seven or eight. His face was not that of a child. It had a careworn, old-mannish look, only relieved by the bright, keen glances of his small, sharp eyes. This sadly overwise face of his, together with the sound of his querulous, high - pitched tones, as he responded glibly to my questions, conveyed to my mind — I knew not why — an acute sense of pain.

Now the ice was broken, I closely cross-examined him, but I am bound to say that there was a ring of truth and reality in his voice, and an unconscious air of sincerity about him, which soon convinced me, ere my inquiries had proceeded far, that I was on the threshold of a revelation.

'Do you mean to say, my boy,' I at length asked for the second or third time,' that you really have no home at all, and that you have no father or mother or friends?'

'That's the truth, sir. I ain't tellin' you no lies.'

'Where did you sleep last night?' I added.

' Down in Whitechapel, along o' the 'aymarket, in one o' them carts filled with 'ay.'

' How was it you came to the school?'

"Cos, sir, I met a chap as I know'd, and he tell'd me to come up 'ere to the school, to get a warm; an' he sed p'raps you'd let me lie nigh the fire all night.'

'But,' I said, 'we don't keep open all night.' 'I won't do no 'arm, sir,' he repeated, 'if only you'll let me stop. Please do, sir.'

It was a raw winter night, and the sharp and bitter east wind seemed to pierce to the very bone, no matter how snugly one was wrapped up. I looked at the little lad whom I now know the Lord had sent me, and could not but see how ill-prepared he was to resist the inclement weather. My heart sank as I reflected, 'If all that this poor boy says is true, how much he must have suffered!'

Then, too, for the first time in my life, there rushed upon me with overwhelming force this thought: 'Is it possible that in this great city there are others also homeless and destitute, who are as young as this boy, as helpless, and as ill-prepared as he to withstand the trials of cold, hunger, and exposure? Surely it cannot be possible, I thought, that to-night there are MANY SUCH in this great London of ours, this city of wealth, of open Bibles, of Gospel preaching, and of Ragged Schools I I turned to the poor little fellow who stood anxiously awaiting my decision.

'Tell me, my lad,' I asked at length, 'are there other poor boys like you in London without home or friends?'

A grim smile of something like wonder at my ignorance lighted up his face as he promptly replied:

'Oh! yes, sir; lots — 'eaps on'em; more 'n I could count.'

This was too much of a bad thing. The boy really must be lying! At any rate, I resolved to put the matter to an immediate test. Surely facts would not bear the boy out! So I asked: 'Now, if I am willing to give you some hot coffee and a place to sleep in, will you take me to where some of these poor boys are, as you say, lying out in the streets, and show me their hiding-places?'

My challenge was promptly accepted.

Would he? Wouldn't he just!

I know not what visions of Elysium came into that poor boy's mind at the bare mention of the warm meal and cosy shelter; but a ravenous, almost wolfish, expression stole over his face as he spoke. He nodded his head in rapid assent, and when I said, 'Now, my boy, come along,' he obeyed with wonderfully quickened steps.

He had not much to say on the way to my dwelling, which was close by the London Hospital, but he kept very near me, his little bare feet going patter, patter, on the cold pavement, his poor rags pulled tightly across his chest, and a wretched apology for a cap drawn over head and ears. He was the very picture of misery and neglect, and I felt almost stunned by the reflection — SUPPOSE, AFTER ALL, HE SPEAKS THE TRUTH! At last we reached my rooms. It was not long before the promised coffee was ready, and I lost no time in getting my ragged pupil placed at the table opposite me. Poor little man! He had at least told the truth about his hunger. How ravenously he ate and drank 1 I almost feared to supply him, with such voracity did he swallow the food. But the hot, sweet coffee put new vigour into his cold little frame. I could see him visibly brightening, and the food and warmth served quickly to loosen his tongue.

He was ready with his history as we sat together, partly in reply to questions, but more often in the form of statements volunteered in the fullness of his grateful heart. I found him to be withal a quaint little vagabond, and his sharp witticisms more than once disturbed my gravity. But there was a sad undercurrent of miserable recollections which occasionally came to the surface. Jim Jarvis's story was given somewhat in the following fashion:—

'I never knowed my father, sir. Mother was always sick, an' when I wor a little kid' — (he did not look very big now!) — she went to the 'firmary, an' they put me into the school. I wor all right there, but soon arter, mother died, an' then I runned away from the 'ouse.'

'How long ago was that?'

'Dunno 'zactly, sir; but it's more'n five year ago.'

'And what did you do then?'

'I got along o' a lot of boys, sir, down near Wapping way; an' there wor an ole lady lived there as wunst knowed mother, an' she let me lie in a shed at the back. While I wor there, I got on werry well. She wor very kind, an' gev me nice bits o' broken wittals. Arter this I did odd jobs with a lighterman, to help him aboard a barge. He used me werry bad, and knocked me about frightful. He often thrashed me for nothin', an' I didn't sometimes have anything to eat; an' sometimes he 'd go away for days an' leave me by myself with the boat.'

'Why didn't you run away, then, and leave I?' I asked.

'So I would, sir, but Dick — that's his name, they called him "Swearin' Dick" — one day he thrashed me awful, an' he swore if ever I runned away, he'd catch me, an' take my life; an' he'd got a dog aboard as he made smell me, an' he telled me if I tried to leave the barge the dog 'ud be arter me; an', sir, he were such a big, fierce un I Sometimes, when Dick were drunk, he 'd put the dog on me, "out o' fun," he said. And look 'ere, air, that's what he did wunst.'

And the poor little fellow thereupon pulled aside some of his rags and showed me a long, scarred, ugly mark, as of teeth, right down his leg.

'I stopped a long while with Dick,' he continued; I dunno how long it wor. I'd have runned away often, but I wor afeared. One day a man came aboard when Dick wor away, and said as how Dick was gone — 'listed for a soldier when he wor drunk. So says to him, "Mister," says I, "will yer 'old that dog a minute?" So he goes down the 'atchway with him, an' I shuts down the 'atch tight on 'em both; and I cries, "'Ooray!" an' off I jumps ashore, an' runs for my worry life, an' never stops till I gets up near the Meat Market; an' all that day I wor afeared old Dick's dog 'ud be arter me.'

'Oh, sir,' continued the boy, his eyes now lit up with excitement, it wor foine, not to get no thrashing, an' not to be afeared of nobody. I thought I wor going to be 'appy all the time now, 'specially as people took pity on me, an' gev me a penny now an' then. One ole lady as kep' a tripe and trotter stall gev me a bit when I 'elped her at night to put her things on the barrer, an' gev it a shove home. But the big chaps on the streets wouldn't let me go with 'em; so I took up by myself.'

'Well,' said what about the police I Didn't they catch you and put you in the workhouse?'

'Oh, sir, the perlice wor the wust; there wor no getting no rest from 'em. They always kept a-movin' me on. Sometimes, when I 'ad a good stroke of luck, I got a thrippenny doss, but it wor awful in the lodgin'-houses. What with the bitin' and the scratchin', I couldn't get no sleep; so in summer I mostly slep' out on the wharf. Twice I wor up afore the beak for sleepin' out, The bobbies often catched me, but sometimes they'd let me off with a kick, or a good knock on the side of the 'ead. But one night an awful cross fellow caught me on a doorstep, an' he locked me up. Then I got six days at the work'us, and the beak said if I comed there again he 'd send me to gaol. Arter that I runned away. Ever since I've bin in an' out, an' up an' down where I could; but since the cold kem on it's been werry bad. I ain't 'ad no luck at all, an' it's been sleepin' out hungry most every night.'

'Have you ever been to school?' I asked.

'Yes, sir. At the work'us they made me go to school, an' I've been into one on a Sunday in Whitechapel. There's a kind genelman there as used to give us toke afterwards.'

'Now, Jim,' I said, would you like to go into a comfortable Home, and always have plenty to eat and drink, and have kind friends to teach you and take care of you?'

'That 'ud suit me, sir, and no mistake.'

'Well, I will see what can be done for you to-morrow. But you know there is another world, brighter and more beautiful than this, where there will be no more hunger or cold, and where little boys will never be beaten and ill-treated. Do you know what that is called?'

'Ah, that's 'eaven, sir!'

'Yes, Jim; wouldn't you like to go there?' and I added, 'Every one who goes there must love Jesus. Have you ever heard of Him, Jim?'

There was a quick nod of assent. The boy seemed quite pleased at knowing something of what I was talking about.

'Yes, sir,' he added; I knows about Him.'

'Well, who is He? What do you know about Him?'

'Oh, sir,' he said — and he looked sharply about the room, and with a timorous glance into the darker corners where the shadows fell — and then sinking his voice into a whisper, he added, 'HE'S THE POPE O' ROME.'

'Whatever can you mean, my lad?' I asked, in utter astonishment. 'Who told you that?'

'No one, sir; but I knows I'm right,' — and he gave his rough little head a positive nod of assertion — ''cos, sir, you see, mother, afore she died, always did that when she spoke of the Pope' — and the boy made what is known as the sign of the cross — 'and one day, when she wor a-dyin' in the 'firmary, a gent wor in there in black clothes a-talkin' to her, an' mother wor a-cryin. Then they begun to talk about Him, sir, and they both did the same.'

'Then because your mother made the same sign with her fingers when she spoke about the Pope and about Jesus, you thought she was speaking of the same person?'

'Yes, sir, that's it'; and the boy gave a nod of pleased intelligence.

I am setting down facts. This was literally all that the poor lad knew of Him who had left heaven that He might seek and save the lost! The greatest event in the world's history was unknown in every aspect and sense to the poor little heathen child who sat before me with widely distended eyes and weird, careworn face, thirsting for knowledge to which he was a stranger, and needing as much as any other child of Adam the solace and comfort which the Gospel of the Divine Love alone could bring. I gave up questioning, and drawing his chair and my own close to the bright fire, I told him slowly, and in the simplest language I could command, the wonderful story of the Babe born in Bethlehem.

After describing the goodness, compassion, and love which the Lord Jesus had shown for everybody, I went on to speak of His trial before Pilate, His cruel scourging, and His crown of thorns. The little fellow, who had been listening all the while with the most intense interest, occasionally asked questions which showed his shrewd application of these events to the only life he knew. He was moved to deep sympathy, for I found he had a tenderly sensitive little heart, despite his rough-and-tumble life. When I came to the sad story of our Lord's crucifixion, and described to him the nails, and the spear, and the gall given to drink, little Jim fairly broke down, and said, amid his tears, 'Oh, sir, that wor wuss nor Swearin' Dick sarved me!'

Then we knelt down together, and I asked the Lord to bless this little Waif of the Streets. When I arose, the poor child's eyes were suffused with tears, and I could not but hope and believe that his young heart, so long neglected, and a stranger even to human love, was being opened to the gentle voice of the Good Shepherd.

It was half an hour after midnight when at length I sallied forth upon my quest, Jim no longer following behind, but with his hand confidently placed in mine.

We passed quickly through the greater streets, and then my little guide led the way into Houndsditch. After partly traversing it, he stopped, and guided me by one or two steps into a kind of narrow court, through which we passed. Here we entered at length what seemed to be a long, empty shed. I found afterwards that throughout the day it was an old-clothes market, called the 'Change.' It ended in a network of narrow passages, leading from and into the well-known noisy Petticoat Lane, the name of which has since disappeared from the London street list.

But when, that night, I passed through these narrow lanes and streets, all was still. The black and dingy shutters of the small, crib-like shops were closed by strong bolts and bars, and no sound did I hear save the echo of my own footsteps.

Once inside the shed, I looked around on every side in search of the lads whom Jim had spoken of. But certainly no one was there save our two selves.

'All right, sir,' said Jim, don't you look no more. We'll come on 'em soon. They dursn't lay about 'ere, cos the p'licemen are so werry sharp all along by these 'ere shops. Wunst, when I wor green, I stopped under a barrer down there' — pointing to a court adjoining — 'but I nearly got nabbed, so I never slep' there agin.'

Meanwhile we had passed through the shed, and Jim, turning to me, with his finger on his lips, said:

"Sh! we 're there now, sir. You 'll see lots on 'em, if we don't wake 'em up.'

We were at the end of our journey. A high dead wall stood in front, barring our further progress; yet, looking hastily around, I could see no traces of lads.

'Where are they, Jim?' I asked, in an undertone.

'Up there, sir,' he replied, pointing to the iron roof of the shed of which this wall was the boundary.

'There' seemed beyond my reach. How was I to get up? Jim made light work of it. There were well-worn marks by which it was possible to ascend and descend — little interstices between the bricks, where the mortar had fallen or had been picked away. Jim rapidly climbed up first, and then, by the aid of a piece of stick which he found on the top and held down for me, I too made my ascent, not without soiled clothes and abraded hands. I found myself standing on a stone coping or parapet. But what was this I saw before me in the gloom?

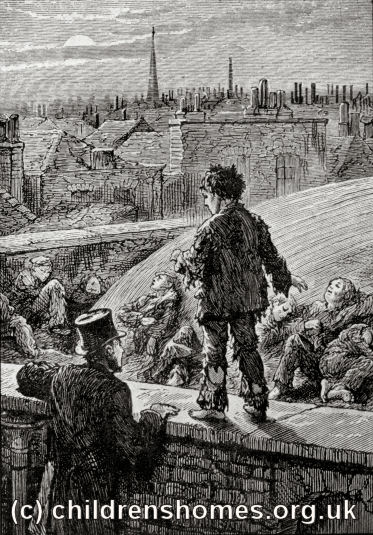

There, with their heads upon the higher part, and their feet somewhat in the gutter, but in as great variety of postures as one may have seen in dogs before a fire — some coiled up, some huddled two or three together, others more apart — lay a confused group of boys out on the open roof all asleep. I counted eleven. No covering of any kind was upon them. The rags that most of them wore were mere apologies for clothes, apparently quite as bad as, if not even worse than, Jim's. One big fellow who lay there seemed to be about eighteen years old; but the ages of the remainder varied, I should say, from nine to fourteen. Just then the moon shone clearly out. As the pale light fell upon the upturned faces of those sleeping boys, and as I realised the terrible fact that they were all absolutely homeless and destitute, and were almost certainly but samples of many others, it seemed as though the hand of God Himself had suddenly pulled aside the curtain which concealed from my view the untold miseries of forlorn child-life upon the streets of London.

Jim took a very matter-of-fact view of the situation.

'Shall I wake 'em, sir?' he asked.

I was overcome with the pain of my own thoughts, and my heart was beating with compassion for these unhappy lads. All I could say in response was, 'Hush! don't let us disturb them.' At that moment, standing there alone in the still silence of the night, with sleeping London all around me, I felt so powerless to help these poor fellows, that I did not dare to interrupt their slumbers. It was to me a revelation and a message. I had made up my mind that, by God's help, this one lad, Jim himself, who had been my guide, should at all costs be cared for and watched over. But to awaken these other eleven boys, to hear their stories — stories doubtless of misery, of lonesomeness, of cruelty, of crime perhaps, and of sin — to find in every word an appeal for help which I could not give, was more than I could bear even to think of. So taking another hurried glance at the wretched and never-to-be-forgotten group — looking down once more at the eleven upturned faces, white with cold and hunger, a sight to be burnt into my memory, and to recur again and again for weeks and weeks, to haunt me until I could find no rest except in action on their behalf — I breathed a silent prayer of compassion and then hurried away, just as one of the sleepers moved uneasily, as if about to awake. We reached the street again. Quite unconscious of the feelings awakened in my mind, Jim eagerly questioned me:

'Shall we go to another lay, sir? There's lots more!' But I had seen enough, and I needed no fresh proof of the truth of his story or any new incentive to a life of active effort on behalf of destitute street lads.

Jim Jarvis shows Thomas Barnardo a rooftop 'lay' of destitute boys, c.1869. © Peter Higginbotham

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Barnardo's 'Making Connections' and Family History Services — for enquiries relating the records of children formerly in the care of Barnardo's and those of other organisations absorbed by them.

Bibliography

- Barnardo, Syrie Louise, and Marchant, James Memoirs of the Late Dr Barnardo (Hodder & Stoughton, 1907)

- Batt, J.H. Dr. Barnardo: The Foster-Father of "Nobody's Children" (S.W. Partridge, 1904)

- Bready, J. Wesley Doctor Barnardo (Allen & Unwin, 1930)

- Higginbotham, Peter Children's Homes: A History of Institutional Care for Britain's Young (2017, Pen & Sword)

- Rose, June For the Sake of the Children: Inside Dr. Barnardo's: 120 years of caring for children (Hodder & Stoughton, 1987)

- Wagner, Gillian Barnardo (Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1979)

Links

- The Barnardo's website.

- The Goldonian Website — memories and information from former Barnardo's children.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.