Separate and District Schools

From the early 1840s, a few poor law authorities began to set up separate schools which provided accommodation and education for pauper children away from the physical conditions of the main workhouse and, as was viewed by many, its 'malign influence' of the young and impressionable. Early separate schools were often in former parish workhouse buildings that a poor law union had inherited, for example the Stepney Union's Limehouse School and the Edmonton Union's Enfield School. Lambeth had a school on Elder Road in West Norwood that dated from 1810.

A prominent proponent of separate schools was Dr James Kay (later better known as Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth). Kay took a particular interest in Mr Aubin's privately run school at Norwood which had over 1,000 residential pupils largely taken from Metropolitan poor-law unions. After the introduction of 'industrial training' (handicrafts for the boys, domestic training for the girls), the banning of corporal punishment, and improved conditions for teachers at the school, great improvements were obtained in the children's performance and morale. As a result the school became a much trumpeted showpiece of public education. Kay proposed a grandiose scheme for establishing a hundred similar 'District' schools across England and Wales each accommodating around 500 children who would be separated from what he saw as the polluting association with the adult workhouse inmates. In such institutions, he claimed, poor law children 'would not be daily taught the daily lesson of dependence, of which the whole apparatus of a workhouse is the symbol... the district school would assume a character of hopefulness and enterprise better fitted to prepare the children for conflict with the perils and difficulties of a struggle for independence than anything which their present situation affords.'

Another influential model was the Bridgnorth Union's school in the village of Quatt. The school, which accommodated around eighty children, was set up in a large house on the estate owned by Bridgnorth Guardian Mr. Wolrych Whitmore. As well as receiving a basic classroom education, the boys cultivated the land and managed farm stock, while the girls did the housework.

Former Quatt School, 2001. © Peter Higginbotham

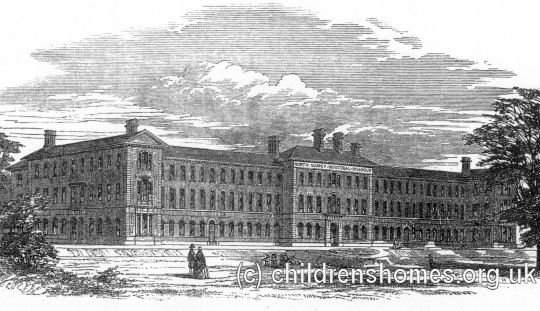

The provision of such industrial training which would equip children for future employment was taken up by many other unions. As well as agricultural and horticultural work, the range of training gradually expanded to include trades such as carpentry, tailoring and shoe-making. Larger separate schools also developed activities such as drill, swimming, and the formation of school bands. Several early examples of large separate schools were located in the north of England: the Manchester Guardians' school as Swinton (1843), the Liverpool Vestry's Kirkdale Industrial School (1843-50), and the Leeds Union's Moral and Industrial Training School (1846-8).

Kirkdale Industrial School, Liverpool. © Peter Higginbotham

Outside London, separate schools were also established by the poor law authorities such as Brighton, Cardiff, Chesterfield and Oxford.

An Act of Parliament in 1844 allowed unions within a fifteen-mile radius (later extended to twenty miles) to form a School District to facilitate the setting up of larger establishments. The anticipated benefits of larger schools included:

- Efficiencies of scale in teaching much larger groups than the small numbers found in many workhouses

- The ability to provide industrial training in a much wider range of subjects than would be feasible in individual workhouses.

- Overall savings in the cost of staff, furniture, books etc.

- Better quality staff who would be attracted to such establishments

However, outside London, only a handful of School Districts (Reading & Wokingham SD, Farnham & Hartley Wintney SD, South East Shropshire, Walsall & West Bromwich) were ever formed.

The Poor Law Board were a little more successful in establishing schools in School Districts in Metropolitan London. In 1849, three School Districts were formed (Central London, South Metropolitan, and North Surrey) which covered ten of the capital's thirty unions. However, a severe blow to the image of large pauper schools occurred in the same year when an outbreak of cholera at Mr Drouet's School at Tooting resulted in the deaths of 180 of its 1,400 resident children. Despite ongoing efforts by the Poor Law Board, it was not until 1868 that three further School Districts (Forest Gate, West London and Finsbury) were created, although Finsbury was dissolved the following year. The Kensington and Chelsea School District was established in 1876 followed by Brentwood in 1877, the latter being dissolved in 1885.

North Surrey District School, 1850. © Peter Higginbotham

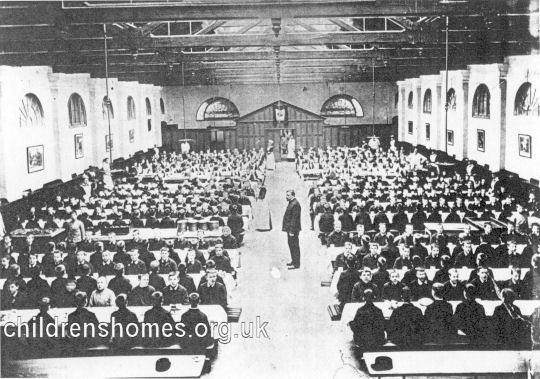

Central London District School at Hanwell, school dining hall. © Peter Higginbotham

By the 1890s, London had five District Schools in operation covering fifteen unions, together with eleven individual separate schools at Bethnal Green, St George-in-the-East, Hackney, Holborn, Islington, Lambeth, St Marylebone, Mile End, St Pancras, Strand, and Westminster. Two Metropolitan parishes — Hampstead and Bloomsbury St Giles — had no schools of their own, with Hampstead sending its children to the Westminster separate school at Tooting, and St Giles to the Strand separate school at Edmonton. By 1900, the Kensington & Chelsea School District and the Shoreditch Union were operating cottage homes sites rather than large schools.

A map of London's School Districts and Unions is shown below — click on the map for more information on a particular area.

© 2004, Peter Higginbotham. Based on data from Great Britain Historical GIS Project.

Former Forest Gate District School, 2002. © Peter Higginbotham

Classroom at the North Surrey District School, early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham

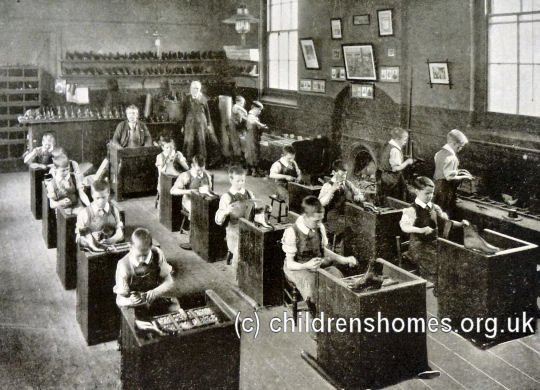

Children at the Schools were give industrial training to make them employable in later life. For the boys, this typically included trades such as carpentry, tailoring, shoemaking and agricultural work. Girls were taught sewing, housework and laundry work, to prepare them for work as domestic servants.

Shoemaking at the North Surrey District School, early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham

Many District Schools had a school band through which, for boys with a musical aptitude, could lead to a career in the army as a military bandsman.

Classroom at the North Surrey District School, early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham

District schools, or "Barrack" schools as they were later stigmatised, were the subject of much criticism. Not only were they expensive to operate, but also proved to be a breeding ground for various infections conditions such as ringworm and an ophthalmic condition known as "the blight". Discipline in the schools would now be considered harsh, as revealed by the accounts of ex-pupils such as Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin's autobiography recounts the story of a boy of fourteen trying to escape from the school by climbing on to the school roof and defying staff by throwing missiles and horse-chestnuts at them as they climbed after him. For such offences there were regular Friday morning punishment sessions in the gymnasium where all the boys lined up on three sides of a square. For minor offences, a boy was laid face down across a long desk, feet strapped, while his shirt was pulled out over his head. Captain Hindrum, a retired Navy man, then gave him from three to six hefty strokes with a four-foot cane. Recipients would cry appallingly or even faint and afterwards have to be carried away to recover. For more serious offences, birch was used — after three strokes, a boy needed to be taken to the surgery for treatment.

Not all such schools received a bad press however. The Hartismere Union's modest District School at Wortham which accommodated around 80 pupils was much commended in an 1880 report by Local Government Inspector Mr Bowyer:

Former Hartismere District School, Wortham. © Peter Higginbotham

By the end of the nineteenth century, separate and district schools had largely fallen out of favour, with a move to establishments of a more domestic style, especially cottage homes and scattered homes, with certified schools and boarding out also widely used by the poor law authorities.

Links

- www.workhouses.org.uk — The Workhouses Website

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.