Naval Training Ships

The earliest naval training ships were run by the The Marine Society, founded in 1756 by Jonas Hanway and still in existence. (Hanway was also a governor of the London Foundling Hospital, involved in the founding of the Magdalen Hospital, and the promoter of the 1766 Act to remove young children from London workhouses.) The Marine Society started life recruiting boys and young men for the Royal Navy at the beginning of the Seven Years War against France but, in an effort to reduce desertions, began training its boys before they were sent to sea. In 1786, the Society purchased a merchant ship the Beatty, which was converted to a training ship and renamed Marine Society. In 1876, the Society acquired the training ship Warspite whose intake included boys placed by the workhouse authorities. By 1911, the Society had sent 65,667 men and boys to sea, of whom 28,538 had gone into the Royal Navy.

Training Ship Warspite, 1877. © Peter Higginbotham.

The Royal Navy's own first training ship was HMS Implacable at Plymouth in 1855 followed by HMS Illustrious at Portsmouth. They aimed to give a training in naval life, skills, and discipline to teenage boys (or 'lads' as they invariably called) and, of course, provide a ready source of recruits for Her Majesty's ships. Over the next fifty years, around thirty other training ships were set up by a variety of other organizations, both public and private, and catering for boys from a wide range of backgrounds. Some, like the Warspite and the Arethusa were charitably run institutions aimed at helping the children of the poor. Other establishments ranged from those for fee-paying prospective naval officers on the Worcester and Conway, through those in Poor Law or other institutional care such as the Exmouth. A number of ships served as Reformatories, e.g. the Akbar on Merseyside and the Cornwall on the Thames at Purfleet, or as Industrial Schools, e.g. the Shaftesbury on the Thames at Grays, and the Clio on the Menai Straits.

The Reformatory Ship Cornwall, c.1910. © Peter Higginbotham.

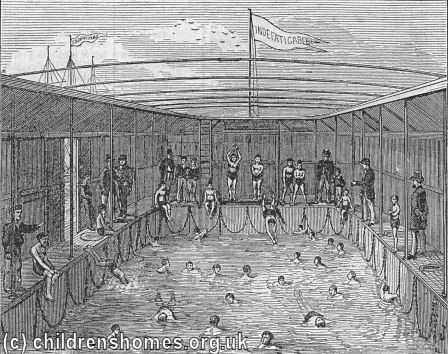

Boys typically joined the ships at the age of eleven or twelve and stayed until they were fifteen or sixteen. Discipline aboard the ships was strict and the birch often used to enforce it. Food was limited in quantity and variety — biscuit, potatoes, and meat were the staples, with occasional green vegetables. Many of the new boys could not swim and needed to be taught — unfortunately some drowned before they mastered the skill! Sleeping accommodation was usually in hammocks, which could be comfortable in the summer but icy-cold in winter.

Swimming training on the Indefatigable, 1874. © Peter Higginbotham

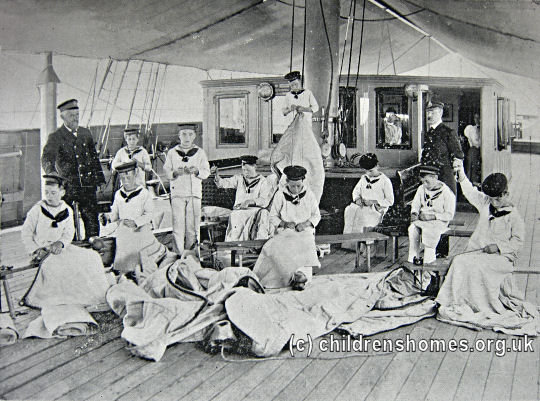

As well as learning nautical skills, boys on training ships were often taught other useful crafts such as tailoring, shoemaking or carpentry.

Sailmaking aboard Industrial School Ship Shaftesbury, off Grays, c.1903. © Peter Higginbotham

Many training ships had a military band where boys with any musical inclinations could develop their talents.

The Empress Band, c.1910. © Peter Higginbotham

Despite their promotion by the Local Government Board, local Boards of Poor Law Guardians appear to have shown some reluctance in using training ships for boys in their care — on 1st January, 1911, the national total of Poor Law boys placed on the ten available ships was only 453. This may have partly due to the cost of maintaining them there, typically eight or nine shillings a week or a one-off lump sum, which was generally a little higher than keeping them in their own local establishments. A payment might also be required for a boy's uniform.

A paper read by Mr Geoffrey Drage at the Central Poor Law Conference in February 1904 extolled the virtues of training ships as a way of improving the prospects of boys from impoverished backgrounds:

The Poor Law authorities, who directly and indirectly encourage and support a training ship like the Exmouth are performing a great national service.

The question which next arises is whether from the point of view of the boys themselves the Guardians are not doing the best that can be done for them in sending them to the Exmouth.

In the first place the life is a healthy one for the boys, their physical development is carefully attended to, their education from an intellectual point of view is adequate, and they receive at the age at which they can most readily profit by it that technical training which at any rate as far as the sea is concerned, can only be properly acquired at an early age. More than all, the so-called stigma of pauperism is removed, and the boys are sent out into the world with a profession of national utility and under the aegis of the name of their training ship, and, when the training ship has an established position, it is an enormous advantage to a boy in after-life, to be able to claim association with it.

The advantages of the Navy as a career can hardly be over-estimated. Quite apart from the great traditions of the service and the universal respect which the uniform inspires, there is the substantial fact that a boy who goes from the Exmouth into a naval training ship can at the age of 40 secure a pension of over £50 for life. What is more, there are few, if any, recorded instances of a blue-jacket receiving relief from the poor law.

In the Merchant Service the career is not quite so satisfactory, but a boy once launched into any of the first-class lines has only to do his work well and his worldly success is assured.

With the advent of steam power, naval crews became smaller and the demand for boys steadily declined, particularly in the Merchant Service. Many of the original wooden training ships also became unseaworthy and their operation gradually moved onto land-based premises. Some survived until the end of the twentieth century but were then forced to close by a reduction in demand for places and in their funding.

Separate pages are available on many individual training ships.

Bibliography

- Carridice, Phil Nautical Training Ships: An Illustrated History (2009, Amberley Press)

- Higginbotham, Peter Children's Homes: A History of Institutional Care for Britain's Young (2017, Pen & Sword)

Links

- None noted at present.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.