Cork County Home / St Finbarr's Hospital, Cork, Republic of Ireland

The Cork County Home had its roots in the Cork Union Workhouse, erected in 1840-41 on a twelve-acre site at Skahabeg North Townland, now Douglas Road, at the south-east of Cork. Like almost all Irish workhouses, the original buildings, at the southern end of the site, were designed by George Wilkinson. A small entrance block at at the north of the complex. The main accommodation block had the Master and Matron's's quarters at the centre, with male and female wings to each side. At its rear, a parallel range of single-storey utility rooms such as bakehouse and washhouse linked via a central spine housing the dining-hall and chapel to the infirmary and 'idiots wards' at the rear of the complex. The buildings were intended to accommodate 2,000 inmates. The premises were subsequently much extended by the addition of a fever hospital, a school, and a variety of other buildings.

The Cork workhouse site is shown on the 1899 map below.

Cork workhouse site, Cork, c.1899.

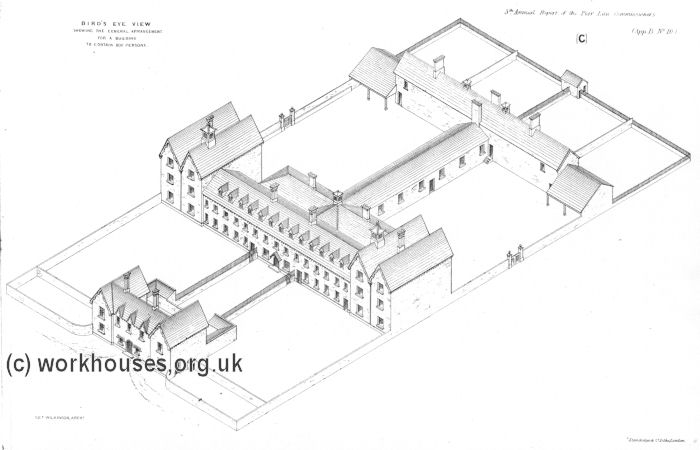

George Wilkinson's model Irish workhouse design. © Peter Higginbotham

Cork's workhouse main block had been demolished. The picture shows the surviving utility range, central spine and infirmary (far left).

Former Cork workhouse from the north-east, 2002. © Peter Higginbotham

In 1870, the Union's Board of Guardians invited the Sisters of Mercy to take charge of the workhouse infirmary. The Sisters already operated a House of Mercy for homeless women and orphans on Fitton Street (now Sharman Crawford Street), Cork. As well as nursing the sick poor, the Sisters taught the workhouse children and also cared for unmarried mothers and their children, a group who formed a significant part of the institution's intake, which also included the homeless, the elderly and infirm, the disabled, and those with mental problems. The workhouse had maternity facilities and was the major provider of institutional care for single expectant women, and unmarried mothers and their children.

Following the creation of the Irish Free State in 1921, the existing Boards of Guardians were abolished and the government appointed commissioners to overhaul the existing poor relief system and formulate a county-based plan for its future administration and operation. Boards of Public Assistance and Boards of Health were formed in each county and the existing workhouse sites allocated to new roles. In most cases, the main building in one of the county's former workhouses was adopted as a County Home, accommodating the elderly poor and infirm, the disabled, and people with various mental conditions, referred to at that time as 'lunatics', 'idiots' and 'imbeciles'. County Homes were frequently also used to house unmarried mothers and their children, and some admitted orphaned or abandoned children. In many counties, former workhouse infirmaries, fever hospitals and other medical facilities were redesignated as County, District, Cottage or Fever Hospitals. The county schemes were formalised by Local Government (Temporary Provisions) Act of 1923, although Cork's had not come into operation at that date and required its own separate legislation the following year. The schemes in each county also continued to evolve after 1923.

County Cork was unusual in that it was divided into three districts, each with its own Boards of Health and Public Assistance. The North Cork District's County Home was in the old Mallow Union workhouse, and West Cork's utilised the former workhouse at Clonakilty. The South Cork District, which included the former Cork Union, took over the Cork workhouse site, part being used as a County Home and part as a District Hospital, later known as St Finbarr's Hospital.

According to a former Cork Guardian, Séamus Lankford, government commissioners making their first appraisal of the Cork workhouse site were met by a dismal scene:

In 1921, the Matron of the Cork workhouse made an urgent appeal to Mr Lankford to provide alternative accommodation for unmarried women and their children outside of the workhouse setting. This led to the establishment in 1922 of the Bessborough mother and baby home. However, of the 76 single mothers living in the workhouse during 1922, eleven opted to, or were eligible for, transfer to Bessborough. Cork's eventual County Scheme did not plan for unmarried women and their children would continue to be accommodated in County Home at Cork, which was to be for 'aged and infirm persons, chronic invalids, idiots and epileptics'. It was envisage that single expectant women would be only admitted to County Home to make use of the adjacent District Hospital's maternity services and then transfer with their babies to the 'auxiliary home' at Bessborough.

In 1927, the Commission on the Relief of the Sick and Destitute Poor reported of Cork that:

In this Home and Hospital the classification leaves much to be desired... in its present condition it is difficult to describe it as either a Home or a Hospital. There were 141 lunatics, imbeciles and idiots in the Home. There were also 23 unmarried mothers and in the nursery 55 children, some of whom were of school age, but getting no schooling. The Scheme does not con~ template either of these classes being in the Home. There is a good maternity department with separate accommodation for the married and unmarried.Between 1922 and 1960, many single women refused to transfer to Bessborough following the birth of their baby. Many more were ineligible for admission to Bessborough because they were on their second or subsequent pregnancy.

Single expectant women, and unmarried women accompanied by a child, who sought admission to the County Home were required to get an admission ticket from the South Cork Board of Public Assistance or one of its agents. Most women secured an admission ticket from local dispensary medical officers who most probably confirmed their pregnancy. The admission ticket ensured that the Board would assume responsibility for the maintenance of the woman and her child in the home. However, the matron of the home frequently admitted single expectant women not having a ticket as she considered that 'to refuse them shelter in their plight would be a grave responsibility'. Around one in four single expectant women admitted to the home were from outside the South Cork District and were asked to contribute to the cost of their maintenance. Such women were usually from the areas covered by the North and West Cork Boards, which were always very reluctant to cover the cost of the women's maintenance in Cork County Home.

In the years 1922-60 several women 'absconded' from the home, i.e. left their babies without arranging for their future care. Although the matron was obliged to notify absconders to the Gardaí it appears that they did not pursue such women with any real vigour. They took the view that abandoned babies were 'kept in safety' in the home and that they had no power to act in these cases. According to the matron, there appeared to be little difficulty passing out of the home unnoticed and that there was nothing she could do if a woman decided to leave the institution without her baby.

Living conditions in the home often left a lot to be desired. In 1931, an inspection of meat being supplied to the home was found to be so bad that it was ordered to be destroyed in a furnace. In 1932, Board of Assistance members visiting the home complained about the quality of the tea in the institution, which was made and served by a 12 year-old boy. They complained that the boy did not know what quantity of tea and sugar to put in the water and concluded that 'it was not fit for pigs'. In 1934, a sample of milk supplied to the home found that it had been diluted by the addition of 18 per cent water.

In 1937, when a married woman sought admission to the home with her three children, a member of the Board of Assistance complained that this 'respectable lady' had been forced to 'consort with women of ill-fame' and that her children were housed in a nursery 'not fit for a kennel'. These comments were subsequently published in the local press and drew angry responses from several board members. The matron of the county home told the board that she did not appreciate that 'alleged defects' in the institution were broadcast in such a manner without attempting to have them remedied in a more satisfactory way. She stated that, in terms of 'cleanliness and brightness', the nursery in the home compared favourably with any hospital. The matron stated that single women living in the institution were 'greatly pained by the appellation applied to them' and that the married woman in question had expressed her regret that women living in the home had been degraded by the board member who sought to help her and her family. The Board investigated the allegations and concluded that they were unfounded and a 'gross misrepresentation' of conditions in the county home nursery.

The home could be a violent place. Assaults in the home and other criminal proceedings where the defendant was living in the home were frequently recorded in local newspapers from the 1920s to the 1950s. Reports of drunk and disorderly inmates were common and women living in the home were regular victims of physical assault. On one occasion, a woman smashed 38 windows in the institution and physically assaulted another woman. Another was admitted drunk and assaulted a woman. Many attempted suicides were reported — inmates cut, or attempted to cut, their own throats open in front of other residents. Others threw themselves from open windows. In one incident, a male inmate killed an elderly male resident and a member of staff by repeatedly hitting them both with an iron drawn from a fire.

n 1949, an inter-departmental committee was established to examine conditions in county homes. The committee reported that although buildings were generally 'sound and spacious' they were 'lacking in comfort and amenities'. The committee found that county homes were 'cheerless and badly furnished', that wards were large with unplastered walls, no ceilings, rough floors, poor beds and bedding, with few chairs, lockers, dressing tables or mirrors and that the general atmosphere in the institutions was 'depressing'. The committee reported:

Regarding accommodation provided for unmarried mothers and children in county homes the committee reported that conditions were 'equally unsatisfactory'. The committee stated that the county home environment was 'most unsuitable' for children and that 'nurseries were rough, poorly furnished and lacking in elementary playing facilities'. The committee stated that in some county homes it was not possible to properly segregate children from adult patients and recommended that separate institutions should be established to house unmarried mothers with children younger than the normal boarding out age (2 years). The committee also recommended that local authorities should consider employing unmarried mothers in county homes when their children were boarded out 'so as to aid in their rehabilitation'. However, the committee reported that there was some reluctance on the part of county home authorities to 'get rid' of unmarried mothers as matrons of the homes relied 'almost wholly' on these women to undertake the 'burdensome and menial work' necessary for running 'large institutions' such as county homes. Matrons told the committee that the removal of unmarried women from county homes would make it impossible to run the institutions. The committee reported that unmarried women engaged in 'menial duties' incidental to the running of county homes without pay. They further reported that accommodation for unmarried mothers in county homes were 'the worst furnished and most unattractive in the institutions' and that their treatment while living in county homes led them to develop 'a soured and distrustful attitude to society generally'.

Most women leaving the home either returned to their family home with their children or arranged for their future care through the boarding out system or by making private arrangements with a nurse mother. A total of 340 women transferred to Bessborough. If a woman sought to make private arrangements with a nurse mother to look after her baby, she could do so herself or use an intermediary such as the Catholic Women's Aid Society (CWAS). The CWAS was set up in 1919 by Sister Laurentia, a member of the Sisters of Mercy convent attached to the Cork County Home. She set up the CWAS in response to a number of high profile court cases where nurse mothers were charged with neglecting and causing the death of 'illegitimate' children they had been paid to care for. It appears that when the lump sum received for a child's care was spent many nurse mothers lost interest in the child and their wellbeing. Under the CWAS scheme, a woman deposited £60 to the CWAS bank account and handed over her infant and the deposit receipt to Sister Laurentia. Sister Laurentia then sourced a suitable nurse mother for the infant and paid her the £60 over three years in twelve quarterly instalments.

The County Hospital section of the site became known as St Finbarr's in about 1952. The whole site adopted the St Finbarr's name in the 1960s.

In January 2021, Ireland's Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation made its final report, which included an examination of the operation of the Cork County Home. Between 1922 and 1960, 13,283 women were admitted to the County Home as maternity cases. Of these, 10,965 were married women and 2,318 were unmarried women. Of the latter, 2,241 were first-time pregnancies, 64 were second pregnancies, and the remainder as third or more pregnancies. Up until 1930, the number of single women entering the home as maternity cases was twice that of married women. The number of married women using maternity services in the institution increased from 60 in 1930 to 1,084 in 1960. This reflected a general increase institutional maternity cases and births, coupled with a shortage of beds in the city's maternity hospitals. Conversely, the number of single women using the institution's maternity services decreased from a high of 98 in 1926 to an average of 14 in the years 1957 to 1960. In the 1950s, when the Department of Health was trying to raise the status of County Homes as institutions for the elderly and the chronic sick, it made greater efforts to removing unmarried mothers from Homes. At the same time, the Sacred Heart Sisters, who ran the Bessborough home, also agreed to admit single women on their second or subsequent pregnancy.

Followed the opening of the maternity hospital at Bessborough in 1933, there was a significant drop in admissions to the County Home, suggesting that more single expectant women were seeking admission directly to Bessborough rather than to the County Home. This trend reversed in the mid-1940s when there was an increase in the number of children born to single women and there was a shortage of places at the Bessborough and other mother and baby homes such as Sean Ross and Castlepollard. Admissions of single expectant women to the County Home began to decrease again from 1949. In 1958 a new maternity hospital opened on the site. While single expectant women continued to be admitted to the institution in the 1960s and later, they only used the maternity services and were discharged a few days after giving birth.

The age of admission to the County Home ranged from 14 to 50 years, the average being 24 years. Single women aged between 18 and 29 years accounted for 81 per cent of admissions while 5 per cent were 17 years or younger. The remaining 14 per cent were women aged between 30 and 50 years. Of the 2,318 single women admitted to the Cork County Home, 98 per cent were recorded as a domestic servant, factory hand or other unskilled worker.

The average death rate among 'illegitimate' infants and children born in or admitted to Cork county home and district hospital in the years 1921-60 was around 20 per cent. However, a death rate of 39 per cent was recorded in 1935 which suggests that two in every five 'illegitimate' children born in or admitted to the institution in that year died. The relatively high death rate of almost 35 per cent recorded in 1944 was a consequence of the increased admissions of single expectant women due to the closure of Bessborough that year. In 1948, and due to the introduction of antibiotics, infant and child mortality in the institution began to decrease. However, a more marked decline in mortality can be observed from 1951 when Dr R G Barry opened the city's first paediatric unit at St Finbarr's Hospital.

p>The unclaimed remains of those who died in the home were buried at Cork District Cemetery at Carr's Hill, Cork, which was owned and operated by the South Cork Board of Assistance.Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Cork City and County Archives, 33a Great William O'Brien Street, Blackpool, Cork. Cork Archives has produced a detailed catalogue of its workhouse-related holdings. Its County Home records include: Combined County Home and District Hospital Indoor Relief Registers (1921-60); County Home, Matrons' Journals (1927-45); South Cork Board of Public Assistance Minutes (1924-42); Cork Board of Public Assistance Managers' Orders (1942-69); South Cork Board of Public Assistance files — Records of deaths in Cork County Home and Hospital (1931-40); the original admission tickets given by the County Home Matron to single expectant women transferring to Bessborough (1922-60).

Bibliography

- Mahony, Colman O Cork's Poor Law Palace (2005)

Links

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.