Introduction

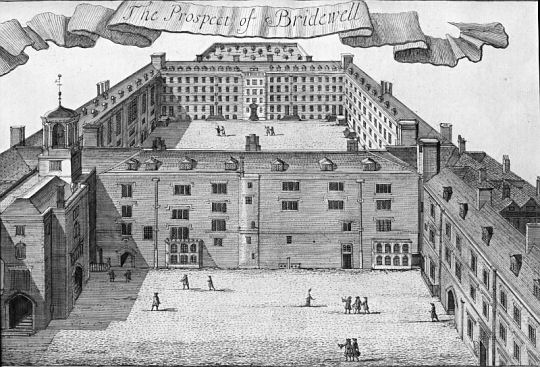

The organised provision of residential care for children who were orphaned, abandoned, impoverished, abused, or otherwise in need of shelter and protection, goes back to at least the sixteenth century. One early establishment was Henry VIII's Bridewell Palace, given to the City of London in 1553 by his successor, Edward VI, for use as an orphanage and also as a place of correction for the 'disorderly poor'.

Bridewell Palace.

Another early institution was London's Foundling Hospital, founded by Thomas Coram in 1739, which provided a home for infants found on the streets, or deposited at the Hospital's gates by their mothers, in a basket placed there for the purpose. The institution was supported by many of the well-to-do, including the artist, Gainsborough, and the composer, Handel.

Coram's Foundling Hospital, c.1900. © Peter Higginbotham

In the second half of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a number of other philanthropically funded homes were established in London. They included the Orphan Working School (1758), the Female Orphan Asylum (1758), the St Pancras Female Orphanage (1776), the Home for Female Orphans (1786) and the London Orphan Asylum (1813). Unlike the Foundling Hospital, these institutions were very restricted in their entrance criteria. Entrants usually had to be of legitimate birth, orphans (i.e. at least one parent dead), physically fit, and not in receipt of poor relief.

Orphan Working School, Hampstead, 1840s. © Peter Higginbotham

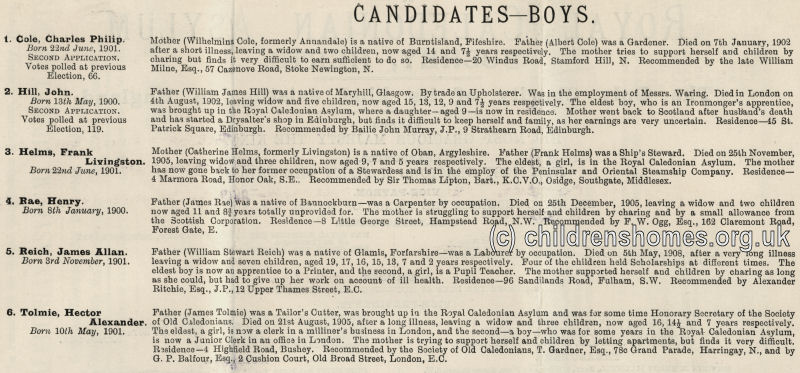

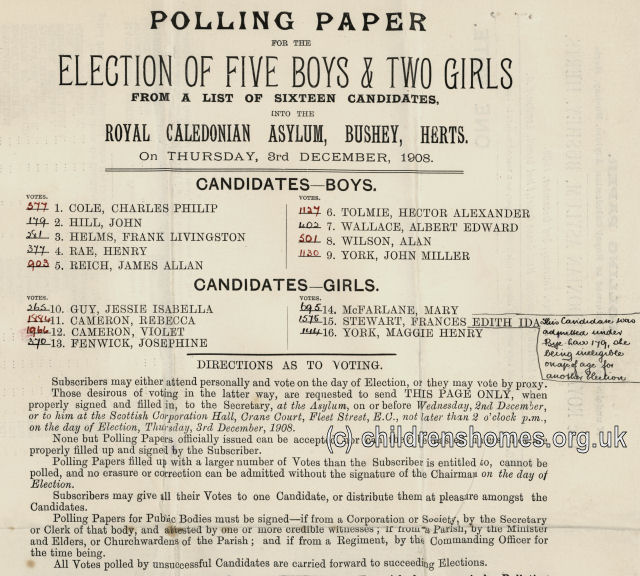

Entry to many of these homes was by a six-monthly election process where donors to the institution's funds voted for their favoured candidates from a list of applicants. Part of the candidates list and polling paper from the Royal Caledonian Asylum's November 1908 election are shown below. The polling paper has been filled in to show the results of the poll.

Royal Caledonian School candidates list, Bushey, 1908. © Peter Higginbotham

Royal Caledonian Asylum polling paper, Bushey, 1908. © Peter Higginbotham

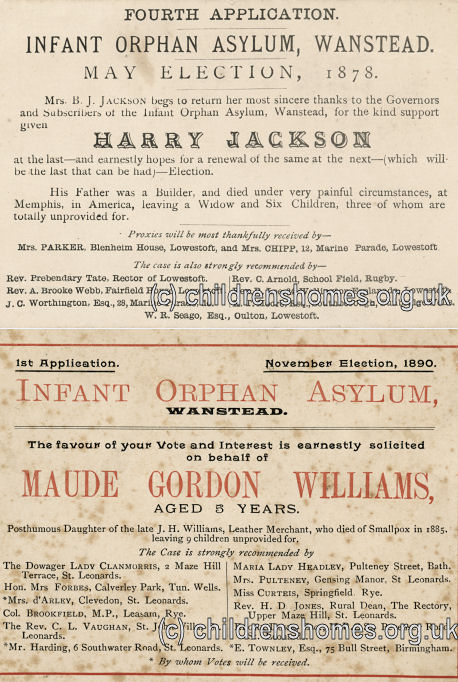

The voters in such elections were often lobbied by the supporters of a particular candidate using cards which the applicant's situation. Here is an example from the Infant Orphan Asylum at Wanstead.

Infant Orphan Election lobbying cards. © Peter Higginbotham

Concern for children involved in crime, either through their own activities or those of their parents, led to the opening of the Philanthropic Society's reforming institution in Southwark in 1788. In 1849, impressed by the success of the 'agricultural colony' for delinquent boys at Mettray, near Paris, the Society set up a Farm School for convicted boys at Redhill in Surrey. Like Mettray, the School housed its inmates in 'family' groups under the supervision of 'house parents'.

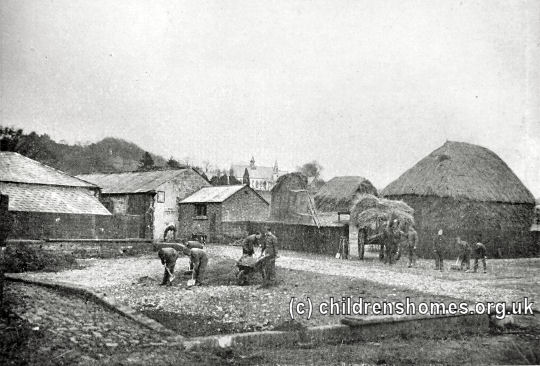

Rickyard at Philanthropic Society's Farm School, Redhill, c.1920. © Peter Higginbotham

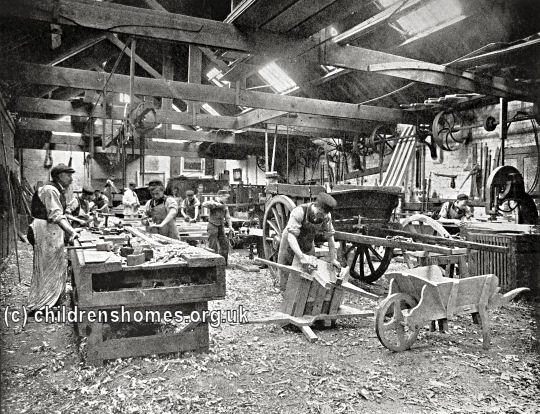

In the 1850s, the growing provision of charitably run reformatories led to the legal recognition of Reformatory Schools where juvenile offenders could be committed by the courts. A few afterwards, a similar status was given to Certified Industrial Schools where children involved in matters such a begging and vagrancy, or who were considered in moral danger, could be placed alongside 'voluntary' cases. The homes provided firm discipline together with training in trades such as carpentry, tailoring, shoemaking, agricultural work and, for girls, domestic activities such as housework and laundry work. In 1933, Reformatories and Industrial Schools were replaced by Approved Schools which, in turn, gave way to local authority run Community Homes in 1969.

Carpentry workshop at Netherton Reformatory for Boys, early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham

A considerable number of children were given a home by the poor relief system. Under the 'Old Poor Law', prior to 1834, little special provision was made for destitute children who entered workhouses. One notable exception came through Hanway's Act of 1767 which required that all London workhouse children below the age of four years should be nursed in the country at least three miles from London and Westminster. Such children were usually placed in establishments variously known as 'branch workhouses', 'infant poorhouses' or 'baby farms'.

The Infant Workhouse (right) at Barnet, used by St Andrew's (Holborn). © Peter Higginbotham

Within a decade of the passing of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act (the 'New Poor Law'), the central authorities had begun promoting the idea of housing pauper children in their District Schools, away from what was viewed as the 'taint' of the workhouse. The Boards of Guardians who administered poor relief in each local poor law union area showed little enthusiasm for the scheme and only few of the proposed Separate (or District) Schools were ever set up.

The South-East Shropshire District School at Quatt. © Peter Higginbotham

In the 1870s, several poor law unions who, like the Philanthropic Society, had been impressed by the 'family group' organisation of continental institutions such as the Mettray colony, and the Rauhe Haus in Germany, began experimenting with what became known as cottage homes. These were typically village-style developments, often set in rural locations, where the children lived in a number of houses, each supervised by a house parent. Cottage home sites often included a school, church, infirmary, workshops, end even a swimming pool.

Poplar Union Cottage Homes, Hutton, Essex, c.1920. © Peter Higginbotham

Another type of accommodation, known as scattered homes, began to be used in the 1890s where the family-style groups of children were placed in ordinary houses spread around a town or city. Children in such homes went to local schools and, it was said, were much better prepared for their adult life.

Sheffield Union scattered homes, c.1896. © Peter Higginbotham

The Victorian era saw the emergence of a large number of homes run by on a charitable basis by individuals, local groups, and national organisations. The most well-known of these were Dr Barnardo's Homes (traditionally dated as being founded in 1866), the National Children's Home (NCH) (founded 1869, now Action for Children), and The Waifs and Strays Society (1881). Roman Catholic Diocesan organisations also operated many homes but had no national umbrella body.

National Children's Home at Edgworth, c.1910. © Peter Higginbotham

Some of the larger charitably-run sites adopted the cottage homes model, such as Girls' Village Home at Barkingside in Essex, opened by Thomas Barnardo in 1873.

Girls' Village Home, Barkingside, c.1910. © Peter Higginbotham

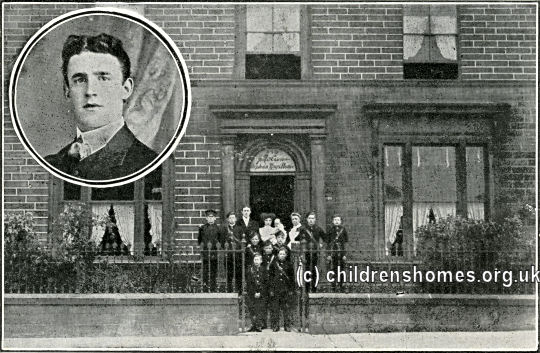

Numerous local institutions were founded by energetic and committed individuals or set up by through gifts or bequests. These ranged in size from a small terraced house caring for a handful of children, to the massive site at Bristol established by George Muller, where two thousand could be accommodated. Religious motivations were generally at the heart of these activities, and a belief that rescuing a child from poverty or abuse was a prerequisite to saving its soul. Religious teaching and worship often featured prominently in the daily life of such homes.

Dr Nolan's Orphan Boys' Home, Bradford, c.1910. © Peter Higginbotham

One of George Muller's 'Orphan Homes' at Ashley Down, Bristol, 2013. © Peter Higginbotham

Some children's homes catered for particular categories of children, such as babies or the physically disabled.

Barnardo's Home for Incurables, Bradford, c.1905. © Peter Higginbotham

Homes were also set up by particular trades or professions such as seamen, the police, or railway workers, to house the children of members who had died while in employment. These homes were often funded by subscriptions from members of the particular occupation or their employers and could enjoy a better and more reliable income than those run purely on charitable donations. Some establishments, such as the Commercial Travellers' Schools, at Pinner, were even on a par with a well-appointed public school.

London and South-Western Railway Orphanage, Woking, c.1909. © Peter Higginbotham

The Second World War disrupted the activities of many children's homes. The residents of homes considered to be in danger of enemy attack were evacuated to temporary premises in safer areas. During the war, a number of homes were converted for use as nurseries. A surge in illegitimate births during the war also resulted in increased demand for homes for babies and young children.

Barnardo evacuees at Comlongan Castle, Dumfries, 1942. © Peter Higginbotham

The post-war years were marked by the beginnings of a change in attitude towards institutional children's care. An important impetus to this was the 1946 Curtis Report which concluded that for children without parents or a satisfactory home, adoption was proposed as the best option, with fostering the next best. If a child had to undergo institutional care, then this should be in small homes of no more than twelve children. Children in such homes should be also encouraged to maintain contact with relatives and to develop friendships outside the home. The Curtis Report's proposals formed the basis of the 1948 Children's Act which also established children's departments in every local authority.

Many of the organisations running children's institutions were slow to come to terms with these changes, even when a decline in demand for places began to make an increasing number of their homes unviable. Reflecting the Curtis Report's proposals, there was a move away from the large orphanage-style institution towards the 'family group' home, supervised by a married couple, and housing boys and girls of a mix of ages. Local authority children's departments, who inherited the stock of homes originally set under the poor law, also set up many new family-group homes.

By the late 1960s, however, many of the long-standing children's care providers were beginning to reorientate themselves — a change reflected in 1966 by what was then known as 'Dr Barnardo's Homes' shortening its name to just 'Dr Barnardo's'. These charities also began explore new areas where the needs of children were not met. In addition to adoption and fostering, these included more specialised work with groups such as the physically handicapped, intellectually impaired, emotionally disturbed and behaviourally maladjusted. By the end of the century, the household names such as the National Children's Home and Barnardo's who had run homes for parentless or destitute children more than a century, no longer did so.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.