The Shaftesbury Homes and Arethusa

The Origins of the Society

In 1843, a solicitor's clerk named William Williams took a train journey from Paddington to the West Country. His attention was caught by a noisy group of boys who, he discovered, were cold, dirty, miserable, chained together, and being transported to Australia as convicts. Determined to do something to help the plight of such boys, he founded a 'ragged school' in the St Giles-in-the-Fields district of London. St Giles was notorious for an area known as The Rookery, one the dirtiest, roughest and most crowded parts of the capital. The school was located in a hayloft over a cowshed on Streatham Street. Despite its humble origins, the opening of the school marked the beginnings of the major charity that later became known as Shaftesbury Homes and Arethusa.

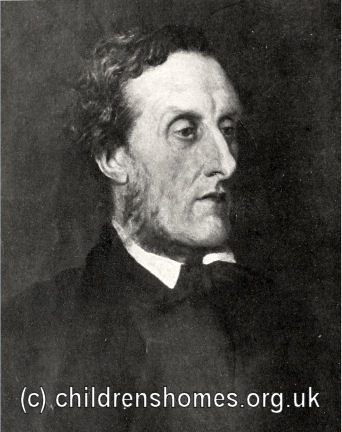

William Williams. © Peter Higginbotham

Ragged schools were not a new idea. Their inception is often linked to the name of John Pounds, a Portsmouth shoemaker who in 1818 provided a free school for the poorest children. Thomas Guthrie helped to promote Pounds' idea of free schooling for working-class children and started a similar school in Edinburgh. A further school was set up in Aberdeen by Sheriff Watson. Although other schools for poor children existed, many often required a small weekly payment. Ragged schools catered for children those whose parents could not, or would not, afford even such a small amount, or who had no family of friends to support them. Such children also lacked enough, or even any, suitable clothes for other schools — hence the name ragged schools. Like Williams' establishment, ragged schools often operated in cheaply rented run-down buildings and were staffed by volunteer teachers who worked unpaid in their spare time. As well as a basic education and religious instruction, the schools usually provided some training in manual trades to try and help their pupils find employment.

0

0

John Pounds' Ragged School. © Peter Higginbotham

Initially, the Streatham Street School only had funds to open on Sundays. The School grew steadily, however, and by the end of its first year of operation a total of 23 teachers worked at the establishment. Its pupils included the children of beggars, street singers, crossing sweepers, costermongers and common labourers. Many of the children had to spend time selling watercress and other articles on the streets before they were able to come to the School.

In 1844, the School joined with a number of others in the capital to form an umbrella organisation called the Ragged Schools Union. Later that year, the Right Honourable Lord Ashley Cooper, M.P., later known as Lord Shaftesbury, became the Union's president. He soon met William Williams and the two became good friends.

Lord Shaftesbury, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

An 1849 report on the Streatham Street School showed it in a very positive light:

The School's Committee was constantly on the lookout for larger and more suitable premises, although this proved difficult, partly because of landlords' reluctance to take on such tenants, but also because large sections of St Giles were being demolished and redeveloped. In 1848, the School was forced temporarily to share premises with the Irish Free School in George Street, St Giles. In 1850, the School merged with two other ragged schools in a similar situation, one located at Abbey Place, Little Coram Street, the other in the very disreputable location of Neal's (or Neales) Yard. In 1851, the new body, known as The St Giles and St George, Bloomsbury, Ragged Schools, was operating three establishments. The Abbey Place School operated on weekday mornings in a stable yard. The Neal's Yard School, also based in a stable yard, was for boys. The largest school was on Great St Andrew's Street in Seven Dials and provided a night-school for girls, with a paid mistress; a Sunday school for girls with two paid and several voluntary teachers; and a girls' sewing class.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.