Certified Industrial Schools

Introduction

The provision of institutional care for children was a feature of the poor relief system in England, going right back to 1553 when the Bridewell Palace, a former residence of Henry VIII, was given to the City of London and used to house homeless children (and also adult 'disorderly poor'). In later parish and town workhouses, such as that set up in Bristol in 1698, children often constituted a large proportion of the inmates. They were taught skills such as spinning and weaving, with any income from their work used to contribute towards the cost of their board and lodging. It was also hoped that such children, on becoming adults, would be employable and not be a burden on the rate-payers.

Following the introduction of the New Poor Law, in 1834, a few workhouse authorities set up establishments known as "Industrial Schools" in the 1830s and 1840s. These were specifically for pauper children whose parents were in the workhouse, or orphaned or abandoned children who were in the care of the workhouse.

A number of individuals also set up influential establishments during this period which catered for poor or neglected children:

- Between 1798 and his death in 1838, Thomas Cranfield, a tailor and former soldier, built up an organization of nineteen Sunday, night and infants' schools situated in the poorest parts of London.

- From around 1818, John Pounds (1766-1839), a crippled cobbler in Portsmouth, began giving local poor children free lessons in reading, writing, arithmetic, bible study, carpentry, shoemaking, and cookery.

- In 1841, Sheriff Watson established the Aberdeen Ragged School for boys.

- In Edinburgh, the Rev Thomas Guthrie Promoted the idea of ragged schools through his 1847 pamphlet Plea for Ragged Schools. In the same year, he set up three schools in Edinburgh at which children received food, education, and industrial training.

- In 1844, the Ragged School Union was founded in London with Lord Ashley Cooper (later known as the Earl of Shaftesbury) as its President. The Union eventually had a membership of around 200 free schools.

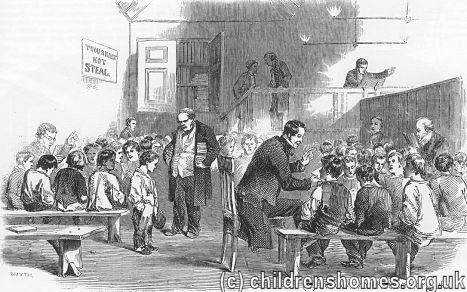

Lambeth Ragged School, 1846. © Peter Higginbotham

Certified Industrial Schools

A new type of establishment emerged in the 1850s, in response to the creation of the Reformatory School system by an Act of 1854. Reformatory Schools were places of detention for convicted juvenile offenders who were first required to spend two weeks in an adult prison. When a campaign to remove this requirement proved unsuccessful, an alternative institution was proposed, the Certified Industrial School, which was aimed at younger and less serious cases, and omitted the prison element. (The Industrial Schools operated by some workhouse authorities never had the prefix 'Certified'.)

Initially, under the Industrial Schools Act of 1857, children aged seven to fourteen who were convicted of vagrancy could placed in a Certified Industrial School until they reached the age of sixteen, regardless of their age of entry. A further Act in 1861 defined four categories of potential entrants: under-fourteens found begging; under-fourteens found wandering and homeless or frequenting with thieves; under-twelves who had committed and imprisonable offence; under-fourteens who parents could not control them.

The first new-style Industrial School is usually said to be that at Feltham, Middlesex — it had actually been founded in 1854 through a private Act of Parliament, although did not come into practical operation until 1859. Other early Schools were opened at: Park Row, Bristol; Pennywell Lane, Bristol; Euston, London; Chelsea, London; Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Manchester, and York. Apart from newly created establishments, some existing ragged schools gained certification to operate as Industrial Schools. Many Industrial Schools received voluntary admissions as well as those committed by the courts. In 1860, central supervision of Industrial Schools passed from the Committee of Council on Education to the Home Office

Another Act in 1866 consolidated and amended the previous legislation and transferred overall responsibility for Reformatories and Industrial Schools to the Prison Authority, with a single Inspector covering both types of establishment. Following the 1869 Habitual Criminals Act, children under fourteen of women twice convicted of "crime" could be sent to a Certified Industrial School.

Cockermouth Industrial School, c.1910. © Peter Higginbotham

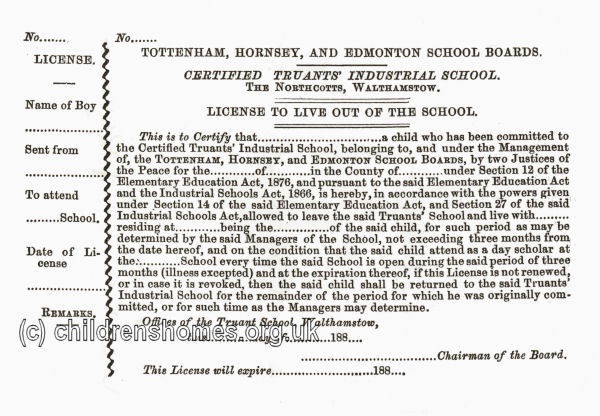

After a child had been in an Industrial School for at least 18 months, he (or she) could be released on a rolling three-month licence to live with a "trustworthy and respectable person". If he escaped from the person with whom he was placed under licence, or refused to return to the School on the revocation or expiry of his licence, he was deemed to have escaped from the School.

In 1911, there were 112 Industrial Schools operating in England and Wales, although only twenty-two were operated by local authorities, the rest being run by charitable and religious groups.

In 1868, the Industrial School system was extended to Ireland and was based on very similar legislation to that enacted in England. Three-quarters of Irish counties eventually established at least one Industrial School.

Day Industrial Schools

Under the 1876 Elementary Education Act, School Boards were authorised to establish Industrial Schools and also Day Industrial Feeding Schools. The latter, usually referred to as Day Industrial Schools, arose from a proposal in 1873 by the Bristol School Board. They suggested that there was a useful role for an institution that provided remedial care and training for children for those failing to attend ordinary Board Schools but that did not entirely remove them from ordinary family life. In the 1876 Act, Day Industrial Schools were specified as being "for those children whose education is neglected by their parents, or who are found wandering or in bad company". The Schools were defined as institutions "in which industrial training, elementary education, and one or more meals a day, but not lodging, are provided for the children" for their "proper training and control". Children typically attended the Schools between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m. and received all their meals there. Satisfactory attendance at a School would allow a child, on licence, to return to an ordinary school. Day Industrial Schools were established almost immediately at Bristol and Liverpool, shortly followed by Gateshead, Oxford, Yarmouth, and a second school at Liverpool.

Bootle Day Industrial School, c.1905. © Peter Higginbotham

Truant/Short-Term Industrial Schools

Another new type of Industrial School that appeared following the 1876 Elementary Education Act was the Truant School. Children up to the age of fourteen who persistently refused to attend elementary schools could be committed by a magistrate. The Schools provided a very strict regime with, for example, playtime replaced by marching drill. After a period of typically one to three months, the offender was released on a renewable licence to attend a normal school. Further truancy resulted in a return to the Truant School, this time for a longer period before release on licence. The first Truant Schools to be established were at London, Liverpool and Sheffield. From 1908, Truant Industrial Schools were renamed Short Term Industrial Schools.

Truant School Licence Form, 1890s. © Peter Higginbotham

The London School Board initially planned that inmates of its Truant Schools should be kept in complete silence, except for during schoolwork, but the Home Office did not approve this proposal. Instead, children were required to perform drill instead of being allowed to play.

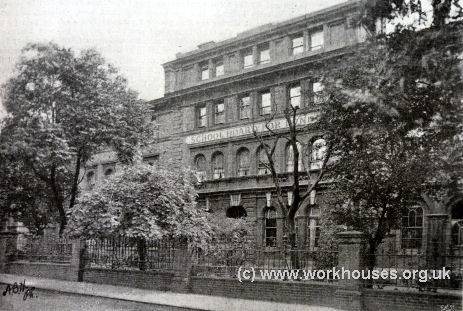

Highbury Grove Truant School, 1895. © Peter Higginbotham

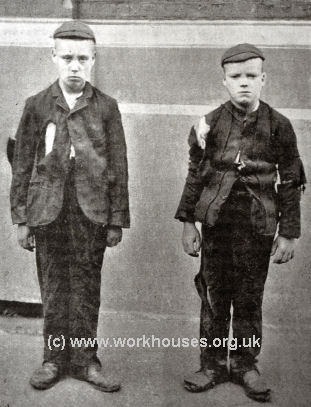

New Arrivals at Highbury Grove Truant School, 1895. © Peter Higginbotham

From 1880, any child under 14 found to be living in a brothel, or living with or associating with common or reputed prostitutes, could be sent to an Industrial School.

Industrial Schools, in common with the Separate or District Schools run by the poor law authorities, often ran a military-style band which gave the boys a musical training and could also lead to a career as a bandsman in the army or navy.

East London Industrial School band, c.1909. © Peter Higginbotham

In the wake of the 1854 and 1857 Acts, Reformatory and Industrial Schools were set up across the country, all of which had to be officially inspected and certified before they could begin operation. By 1875, there were 54 certified Reformatory Schools and 82 Industrial Schools in England and Wales. At the same date, Scotland had 12 Reformatories and 27 Industrial Schools. By 1885, there was a combined total of 61 Reformatories, 136 Industrial Schools, 9 Truant Schools, and 13 Day Industrial Schools. Generally schools took either just boys or girls, and some schools were specifically for Roman Catholic children.

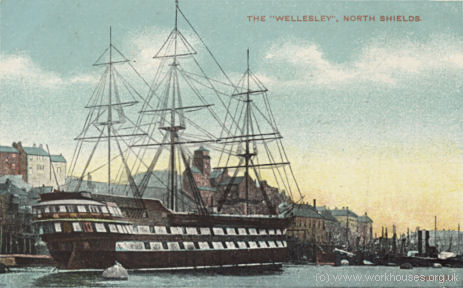

Amongst the Industrial Schools for boys were a number of naval training ships. These included the Formidable in the Bristol Channel, the Wellesley on the Tyne, and the Mars on the Tay.

The Wellesley, c.1910. © Peter Higginbotham

Auxiliary And Working Boys'/Girls' Homes

A final category of establishment was the Auxiliary Home. These were usually small homes linked to larger Reformatories or Industrial Schools and which sometimes catered for particularly difficult cases, or as a half-way house for inmates who were about to leave to go into employment. The latter were often referred as Homes for Working Boys (or Girls).

The majority of Industrial and Reformatory Schools were privately run, often by religious groups. The Schools were not always successful and some closed within a few years.

The 1908 Children's Act

The 1908 Children and Young Persons Act, sometimes referred to as the 'Children's Charter', carried out a major revision of the existing legislation relating to children and introduced a variety of measures for their legal protection. Parents who ill-treated or neglected their children could now be prosecuted. Foster parent now had be officially registered with their local authority. The Act also banned the sale cigarettes to children, their visiting pubs and pawnbrokers, and their employment in dangerous trades like the scrap metal industry.

Children who broke the law were now dealt with by special juvenile courts. However, the 1908 Act still maintained the distinction between Reformatory Schools and Industrial Schools. Reformatory Schools continued to receive youthful offenders below the age of sixteen, while Industrial Schools received children under fourteen found to be destitute, begging or wandering the streets, or whose parents were deemed unfit to look after the them, or who associated with reputed thief or prostitute. The Act included a provision for children to be transferred between the two types of school. A period of probation, supervised by a probation officer, became available as an alternative to being sent to an Industrial School.

Special Industrial Schools

From around 1908, a number of "special" Industrial Schools were certified to receive children with particular conditions such as physical disability (e.g. St Vincent's, Pinner), ophthalmic problems (e.g. St Anne's Special School, Notting Hill), deafness (e.g. Homerton), epilepsy (e.g. St Elizabeth's, Much Hadham), and what was termed "mental defectiveness", (e.g. Pontville Special School, Ormskirk and Besford Court, Defford). Schools were also established for girls who had suffered sexual abuse (e.g. St Winifred's, Wolverhampton and St Ursula's, Teddington).

Over the next two decades, partly as a result of negative publicity in the press about their ill-treatment of children, admissions both to Industrial Schools and Reformatories declined steeply. In 1925, the Home Office set up a Departmental Committee to examine the future of the schools. Its report, issued in 1927, recommended that the distinction between Reformatory and Industrial Schools be abolished and replaced by a single type of establishment to be known as an Approved School. The new Schools were to cater for all classes of neglected and delinquent children. This recommendation came into effect through the 1932 Children and Young Persons Act (slightly revised as part of the 1933 Children and Young Persons Act). Many former Reformatory and Industrial Schools then converted to become Approved Schools.

Records

Since most Industrial Schools were privately run by charitable or religious groups, the survival of their records is rather uneven.

Most of those entering Industrial Schools were placed there by the courts and details of their committal recorded in magistrates' (Petty Sessions) records. These are generally found in the county or metropolitan archives of the place where the sentencing took place — this may be some distance from the institution where the young person subsequently became an inmate. It should be noted that many Industrial Schools also took voluntary admissions, whose details will not appear in court records.

A few of the Schools were run by national charities including Barnardo's, The National Children's Home and the Waifs and Strays Society and their records will form part of each organisation's archives. A similar situation applies to institutions of this type run by other bodies (e.g. religious groups) which still survive and which maintain their own archives. Access to such records may incur a charge and also be restricted to former inmates or their immediate descendants.

Otherwise, the best place to look for any surviving records for these institutions is the county or metropolitan record office covering the area.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Children's Homes: A History of Institutional Care for Britain's Young (2017, Pen & Sword)

- Mahood, Linda Policing Gender, Class and Family: Britain, 1850-1940 (1995, Univeristy of Alberta Press)

- Prahms, Wendy Newcastle Ragged and Industrial School (2006, The History Press)

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.