Boarding Out (Fostering)

Boarding-out was the practice of placing children in the long-term care of foster parents who usually received a weekly allowance for each child staying with them. The system, which is usually said to have originated in Scotland, was seen as the nearest approximation to a 'normal' home life that could be provided by a child-care agency, and was also financially economical compared to institutional accommodation.

The development of boarding-out, or fostering as it is now more usually known, owed much to its adoption by the poor law authorities. The practice first came under official consideration by the central Poor Law Board in 1868. Up until then, the Board had been informally opposed to the system since it handed over the control of children to those whose main aim might simply be to make a profit from the weekly maintenance payments they received. Fears of possible neglect, cruelty or exploitation of boarded-out children made the Board extremely cautious about sanctioning its use. In 1869, the Board asked its inspectors to report on the use of boarding-out in England and Wales. It was discovered that only twenty-one unions in England and Wales used boarding-out, covering a total of 347 children, generally with good results. One union, Warminster, had successfully used boarding-out for more than twenty years. The Board also commissioned a report from one of their inspectors, Mr Henley, on the operation of boarding-out in Scotland. Henley noted some particular attributes of the Scots — their generally good level of education, and the existence of a class of crofters or small occupiers (a class relatively unknown in England) who proved to be good foster parents.

The Board agreed to a wider trial of boarding out and in 1870 issued a formal framework for boarding-out in the form of the Boarding-out Order (1870). The Order specified that:

- A Boarding-out Committee be formed in each union to supervise the boarding-out arrangements — Committees were to have at least three members at least one of which was to be female

- Only orphans and deserted children to be boarded out

- Only children aged between two and ten to be boarded out

- No more than two children to be boarded out in the same home unless brothers and sisters

- No child to be boarded out with foster parents of a different religious persuasion

- Foster parents to sign an undertaking agreeing to "bring up the child as one of their own children, and provide it with proper food, lodging, and washing, and endeavour to train it in habits of truthfulness, obedience, personal cleanliness, and industry, as well as suitable domestic and outdoor work"

- Weekly maintenance fee not to exceed four shillings a week

- No child to be boarded out in a home more than a mile-and-a-half form a suitable school

- No child to be boarded out in a home more than five miles from the residence of a Boarding-out Committee member

A revised order in 1877 prohibited the boarding-out of children with foster parents who were themselves in receipt of poor relief. Further orders were issued in 1889 which also provided for the boarding-out of children outside their own union. In 1885, the Local Government Board appointed a lady Inspector, Miss MH Mason, who along with two female colleagues regularly visited the thousand or so children boarded-out beyond their own union.

By the end of the nineteenth century, around half of the unions in England and Wales were using boarding out, with around 8,000 orphaned or deserted children placed in homes. Although occasional cases of ill-treatment emerged, these were far outweighed by stories of children filled with dread at the possibility of being taken away from their foster homes. Although boarding-out established itself one of the most popular ways of dealing with children in the care of a union, it rarely proved possible to find enough families willing to take on the role. It was also only suitable for children in long-term care — for the many children came and went more quickly, scattered homes were a more suitable solution.

After some initial caution, the use of boarding-out was gradually taken up by the voluntary sector. In 1887, Thomas Barnardo — recognising the benefits of boarding-out both for the children themselves and for relieving the pressure on places in his homes — placed 330 boys with families in "good country homes". Those he chose for boarding-out were the younger ones, aged five to nine, who he felt suffered most from institutional care. The scheme was also limited to "orphans", although this was a term he interpreted rather broadly as having one or both parents dead, or with both parents being deemed unsuitable.

The foster-parents, all working-class, were given a payment of five shillings a week for each child. They were required to have adequate accommodation that offered "satisfactory sanitary conditions, pure moral surroundings, and a loving and Christian influence." They also had to sign a lengthy and detailed agreement as to how the children were to be treated. Regular inspection of the children was originally carried out by a specially employed female physician, with nurses later taking on the role.

A Barnardo's inspector checks the health of boarded-out children, 1930s. © Peter Higginbotham

The experiment proved a success, with the children settling in well and, with a very few exceptions, receiving satisfactory reports with regard to their health and educational progress. Boarding-out was also cheaper than the cost of institutional care and had economic and other benefits for the foster-parents and their communities. As a result, the scheme was expanded and by 1892, more than two thousand Barnardo children were being boarded out. Financial problems led to a fall in numbers in the 1890s, but by the time of Barnardo's death in 1905, over four thousand children were being fostered, about a quarter of those being in Canada. One of the few complaints about the system as that when reaching the age of fourteen, children had to move back to one of the central homes to receive technical or domestic training.

The Waifs and Strays Society's emphasis on placing children in a family environment made boarding-out an attractive option. In June 1883, the Society fostered its first child — Case No. 7, Jane Bellamy — with a family in Wiltshire. Over the next thirty years, around a quarter of the children in the Society's care were fostered each year.

Much of the groundwork in finding foster homes was placed in the hands of local clergy who, together with other suitable people from the area, also supervised the children and submitted reports on them every three months. Regulations for fostering were instigated, based on those used by the Poor Law Unions. These included rules such as:

- Children shall not as a rule be boarded out at a later age than seven years, and in no case at a later age than ten years

- Children shall not, save in special cases, be boarded out with relations or with persons in receipt of relief out of the poor-rates.

- No child shall be boarded out in a house where sleeping accommodation is afforded to an adult lodger.

- In no case shall the weekly sum to be paid to the foster-parents for the maintenance of a child inclusive of lodging, clothing, school-pence and fees for medical attendance, exceed five shillings.

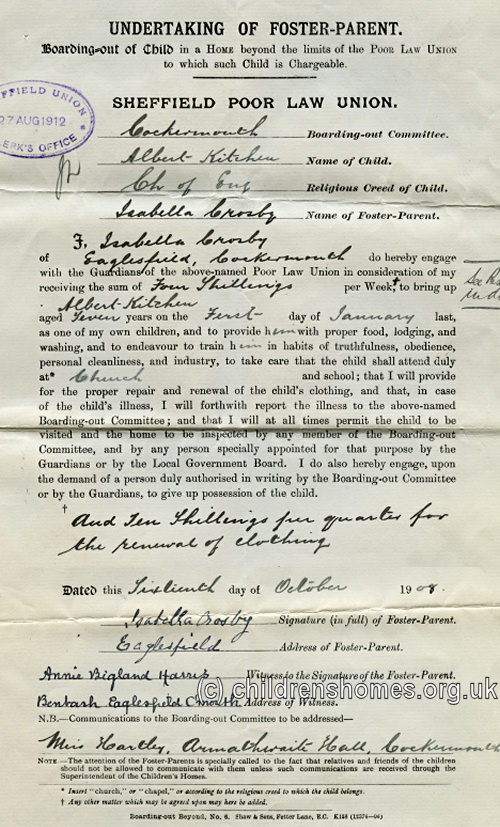

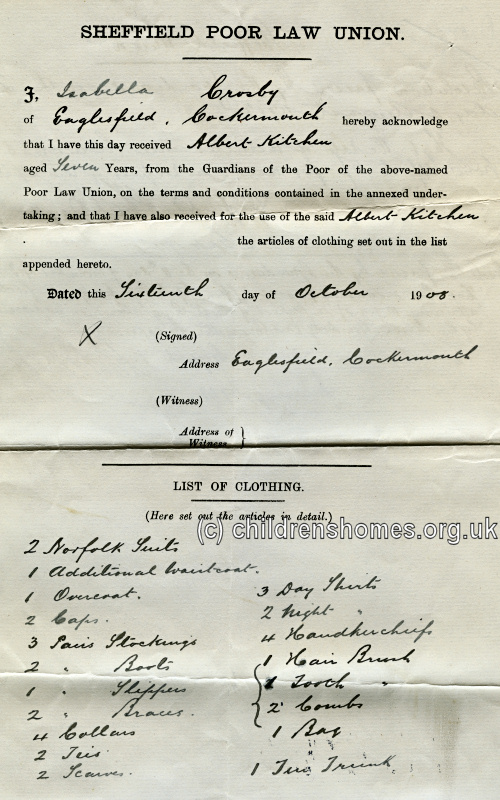

When receiving a child, foster parents entered into a formal contract with the organisation placing it, such as the one below made in 1908 between the Sheffield Poor Law Union and Isabella Crosby of Cockermouth in Cumberland. This also illustrates the long distance that children sometimes travelled to their foster homes.

1908 boarding-out agreement, part 1. © Peter Higginbotham

1908 boarding-out agreement, part 2. © Peter Higginbotham

Despite supervision and regulations, cases of neglect or cruelty occasionally surfaced. In 1893, the Waifs and Strays Society appointed a professional Inspectress who toured the country making unannounced visits to the Society's homes.

After a slow start, the National Children's Home (NCH) also made use of boarding-out. In 1909, of the 7,924 children ever received by the charity, 2,008 were still in its care, of whom 477 (almost 24 per cent) were in foster homes. In line with other agencies, the NCH brought fostered children back into one of its homes before they left its care. The age at which the NCH did this — 7 or 8 years — was much lower than that applied in other organisations.

Of all the various forms of residential care established by child-care agencies, fostering became the one that proved the most durable and continues to play an important role to this day.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Children's Homes: A History of Institutional Care for Britain s Young (2017, Pen & Sword)

Links

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.