Golden Bridge Industrial School for Roman Catholic Girls (St Vincent's), Dublin, Ireland

On 13 July 1880,the Golden Bridge (or Goldenbridge) Industrial School for Roman Catholic Girls was certified to begin operation in premises at St Vincent Street, Golden Bridge, Dublin. Its initial official capacity of thirty places was raised to fifty places at the beginning of 1881. The School was situated on a ten acres of land, including a garden and poultry yard. A well-equipped laundry was also provided. The institution was intended to provide a family-like environment for its inmates. It was superintended Sister Magdalen Kirwan, who was an advocate of the Froebel system, which aimed at the education of the senses in very young children. She was assisted by three Sisters of Mercy, plus five other officers.

The girls were instructed in needlework and the use of sewing and knitting machines. They made their own clothes, and shirts for sale in shops. They were taught cooking and housework, worked in the laundry, were employed in the garden, and had charge of a quantity of poultry.

Adjacent to the School was a Convict Refuge, which had been founded by Sister Kirwan in 1856 to accommodate female convicts. In 1883, the Refuge building was enlarged and converted for use by the Industrial School. Its facilities then included a steam laundry, workrooms, schoolroom, kitchen, dining-hall, large well-ventilated dormitories, dressing rooms, and bathrooms, with its capacity being increased to 90 places. The School's former accommodation was then taken over by the Refuge. Kirwan was given considerable support in her work by the then Viceroy of Ireland, Earl Spencer. Her aim for the Industrial School was 'to educate her pupils specially with a view to make them fitting wives for artisans, giving each a dowry; her object being to create a class of sober, industrious, law-abiding citizens in the next generation.'

In 1885, the School's inspector praised the management of the kindergarten and the girls' china painting. A certificated teacher from South Kensington had been engaged to give lessons in cookery.

By 1890, the School's official capacity had been increased to 150 places.

In around 1897, Sister Kirwan was succeeded as superintendent by Sister M G Howell. She was followed in 1909 by Sister M B Sheehy.

A 1911 inspection report noted that the institution had been divided for the purpose of domestic training into a senior school and a junior school. Classroom lessons now included mental arithmetic, grammar, recitation, geography, drawing and singing. Industrial training included needlework, cookery and laundry work. The girls were given daily drill and did marching and exercises with dumb-bells and bar-bells.

From around 1914, the School was known as St Vincent's.

Golden Bridge Industrial School site, Dublin, early 1900s.

Former Golden Bridge Convent, Dublin, 2014. © Peter Higginbotham

Golden Bridge Convent, Dublin, Dublin, early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham

Surviving section of St Vincent's Industrial School, Dublin, 2014. © Peter Higginbotham

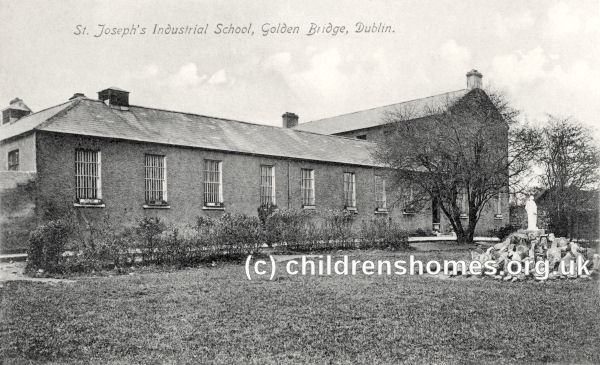

Maps of the early 1900s also show a separate block at the south of the site, identified as St Joseph's Industrial School, perhaps reflecting separate accommodation for the senior and junior girls.

St Joseph's Industrial School, Dublin, early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham

The School continued in operation until 1983. The main School building no longer exists, although the covent, church, and part of the industrial school building survive.

St Vincent's was one of the establishments examined by the Irish Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse. The Commission found that during the 1940s and 1950s, the School was overcrowded and understaffed. The children were mostly under the care of largely unsupervised lay staff who included former residents. Corporal punishment was widely used, even for small misdemeanours, and continued to be used for bed-wetting until the 1970s. From the 1940s to the 1960s, children at the School were occupied in making rosary beads. The demands of the work were found by the Commission to have been excessive, causing the children stress and depriving them of recreational time. The food served to the children during this period was found to be lacking in quality and quantity.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Barnardo's Origins Tracing Service — for people (and their families) who spent all or part of their childhood in an Irish Industrial School and are interested in tracing information about their parents, siblings or other relatives.

- Irish Petty Sessions Court Registers 1828-1912 (available online to subscribers of FindMyPast) include details of committals to Irish Reformatories and Industrial Schools.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Mavis, and Laskey, Heather Children of the Poor Clares (2004, Appletree Press)

- Barnes, Jane Irish Industrial Schools 1868-1908 (1989, Irish Academic Press)

- Dunne, Joe The Stolen Child: A Memoir (2003, Marion Books)

- Rafferty, Mary and O'Sullivan, Eoin Suffer the Little Children: The Inside Story of Ireland's Industrial Schools (1999, New Island Books)

- Touher, Patrick Fear of the Collar: Artane Industrial School — My Extraordinary Childhood (1991, O'Brien Press)

- Tyrrell, Peter and Whelan, Diarmuid Founded on Fear: Letterfrack Industrial School (2006, Irish Academic Press)

- Wall, Tom The Boy from Glin Industrial School (2015, Tom Wall)

- Higginbotham, Peter Children's Homes: A History of Institutional Care for Britain's Young (2017, Pen & Sword)

- Mahood, Linda Policing Gender, Class and Family: Britain, 1850-1940 (1995, Univeristy of Alberta Press)

- Prahms, Wendy Newcastle Ragged and Industrial School (2006, The History Press)

Links

- Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse.

- Glencree Reconciliation Centre (former Reformatory site)

- The Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.