County Home, Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny, Kilkenny, Republic of Ireland

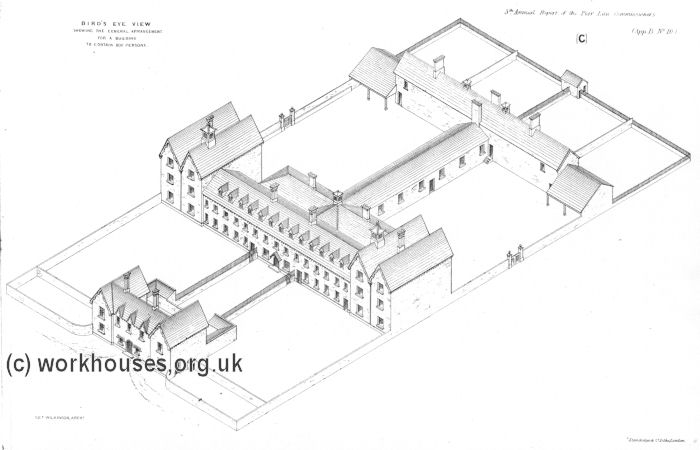

The Thomastown County Home had its roots in the Thomastown Union Workhouse, opened in 1853 on an eight-acre site just to the north-east of Thomastown. Like almost all Irish workhouses, the original buildings were designed by George Wilkinson. There was a single-storey entrance block at the east of the site. The main accommodation block had the Master and Matron's's quarters at its centre, with male and female wings to each side. At its rear, a parallel range of single-storey utility rooms such as bakehouse and washhouse were linked, via a central spine housing the dining-hall and chapel, to the institution's infirmary and 'idiots wards'. The buildings were intended to accommodate up to 600 inmates.

George Wilkinson's model Irish workhouse design. © Peter Higginbotham

The Thomastown workhouse site is shown on the 19010 map below.

County Home site, Thomastown, c.1910.

Former Thomastown workhouse entrance block from the south-east, Co. Kilkenny, 2002. © Peter Higginbotham

From 1888, the Congregation of the Sisters of St John of God provided the nursing staff in the workhouse infirmary.

Following the creation of the Irish Free State in 1921, the Boards of Guardians that administered each union area were abolished and the government appointed commissioners to overhaul the existing poor relief system and formulate a county-based plan for its future administration and operation. Boards of Public Assistance and Boards of Health were formed in each county and the existing workhouse sites allocated to new roles. In most cases, the main building in one of the county's former workhouses was adopted as a County Home, accommodating the elderly poor and infirm, the disabled, and people with various mental conditions, referred to at that time as 'lunatics', 'idiots' and 'imbeciles'. County Homes were frequently also used to house unmarried mothers and their children, and some admitted orphaned or abandoned children. Many former workhouse infirmaries, fever hospitals and other medical facilities were redesignated as County, District, Cottage or Fever Hospitals. The county schemes were formalised by Local Government (Temporary Provisions) Act of 1923. In County Kilkenny, the Thomastown workhouse became the Thomastown County Home. Its remit was to admit and maintain the following people who were eligible for indoor relief — 'aged and infirm persons, chronic invalids, children, expectant unmarried mothers, harmless lunatics and idiots'.

In 1922 was particularly bad year, 9 out the 16 children born (41 per cent) at the home subsequently died. The high infant mortality was, according to the institutional medical officer, due to 'careless and indifferent mothering' and because 'mothers are not sufficiently careful in giving the infants nourishment'. However, an inquiry by a in inspector from the Department of Local Government and Public Health (DLGPH) found that the nursery section of the institution was overcrowded (35 women and 35 infants), understaffed. The lavatory accommodation was insufficient and insanitary. Just one midwife cared for all women and children as well as attending to maternity cases. Infants were removed from the nursery at night and placed in an unheated dormitory, passing through an open yard on each occasion. Bed clothes for unmarried mother were described as wretched and scanty. Amongst the inspector's many recommendations was that the county Board of Health employ an additional nurse with midwifery qualifications. Initially, the Board refused to do so and instructed the Matron to ask 'the nuns' to supervise the nursery and to utilise the services of unmarried mothers living in the home to assist them. The Sisters responded that they had no spare capacity to supervise the nursery. After the Board discovered that the midwife in the institution was not a permanent official, but paid 15s for every maternity case she attended, they agreed to employ a permanent qualified midwife who would also act as assistant matron in the home.

In October 1925, a DLGPH inspection of the home found that 58 children, aged from new-born to over three years old, were sleeping in 32 cots. The inspector, Miss Fitzgerald-Kenny, advised the Board of Health to consider the transfer of 'suitable women' from the home to Bessborough. She told the Board that there was a woman in Thomastown county home with four illegitimate children and that the woman's oldest daughter had been admitted to the home 'with a second illegitimate child'. She told the Board that it was desirable that 'first offenders' should be transferred to a home such St Patrick's, in Cork, 'where their characters would be formed on the right lines and where they would be fitted for the battle of life.' The Board initially sent four 'first time offenders' and their infants to Bessborough. After hearing that they were doing well, the Board transferred a further ten women and their infants to Bessborough.

An inspection in 1927, recorded 38 unmarried mothers living in the home, of whom eight were 'first offenders'. The report found that the water supply to the institution was 'bad' and that bathing and sanitary accommodation there was 'very bad'. Furthermore, the standard of comfort in the home was 'poor' and that little effort was made 'to brighten the lives of the aged and infirm' or to 'reform those who through moral weakness', were obliged to seek shelter there. The report noted that a maternity department attached to the home had insufficient accommodation to cater for the number of women seeking admission.

In 1928, the Kilkenny Board of Health advertised for people living in Kilkenny to consider taking children from the home under the local authority boarding out scheme. The rates of pay were stated as 6s. per week for each child up to 10 years of age, and 3s. per week for those aged 10-15 years. In either case here was also a £3 annual clothing allowance for each child. On 31 March 1929, 52 children were on the county boarded out register, most from the 'class of life' labelled as 'Domestic servants'. During the previous twelve months, fifteen children had been removed from the register: five were returned to Thomastown county home by foster parents; three were 'adopted' by their foster parents; two were claimed by their mothers; two were placed in the Good Shepherd Convent, Waterford (an industrial school) and nine were admitted to hospital.

In April 1942, An 18-month-old girl fell to her death at the home. The child was sitting on a ledge in the home when she fell through an unfastened window. She fell 30 feet and fractured her skull. At the inquest, the woman said that she was in the habit of sitting her child on the window ledge and did not realise that the window was unfastened. One of the Sisters stated that inmates were not allowed take children with them around the house but were supposed to leave them in the nursery in the morning and had to ask permission to remove them from there. The inquest jury returned a verdict of accidental death.

On St Stephen's Day (December 26) 1943, the future Vogue magazine publisher Stephen Quinn was born to a young unmarried mother at the home and lived there for two years before being fostered out in South Kilkenny. Quinn received considerable publicity in 2000 after divoricing his then wife, Kimberly, after she had an affair with British politician David Blunkett.

In 1945, a visiting committee's report on the home stated that 60 or 70 men were in the dining hall at the time of the visit and that the ration was 'meagre' and consisted of 'about three potatoes, a little green cabbage and home cured bacon'. The meat being served was 'large lumps of fat that in any home would be diverted to the offal for dogs and pigs'. In the female dining room, they encountered '12 or 14 unmarried mothers with their babies'. The same state of affairs existed there as 'there was not a pick of food visible, except potato skins and the relics of the pig... The fire was at its lowest ebb with no apparent fresh supply of fuel…the floor was littered with straw.

In November 1945, the Kilkenny County Surveyor, Mr J.C. Coffey, reported that the home had a single vertical boiler which served the kitchen, eight baths, laundry and drying rooms. Its capacity was inadequate to serve the institution and when dinner was being cooked there was little heat available for other purposes. He noted that the baths in particular were seldom supplied with hot water. There was no central heating in the home and the dormitories and wards were heated by small open fires. He recommended that central heating should be installed and that the cooking arrangements, which he described as 'also bad', should be overhauled. Following a further inspection in November 1946, Mr Coffey again drew attention to the primitive nature of the heating and cooking arrangements and highlighted the 'totally insufficient' sanitary arrangements in the institution. At the time of his visit, 250 men, women and children had eight baths, eight W.Cs and 16 wash-hand basins available to them. In addition, he noted that all washing in the institution was done by hand and that the laundry was not equipped with disinfecting or sterilising equipment. He reported that the labour ward in the institution had no electrical sockets, no heating and no sanitary equipment.

In February 1949, the Department of Health (successors to the DLGPH) sent an engineer to the home assess the necessity for the improvements recommended by Mr Coffey and to consider the expenditure involved. The Department advised that the proposal to install a central heating system should be 'deferred, if not abandoned' as few county homes had central heating and that institutions such as sanatoria and regional hospitals should take priority over county homes. In May 1949, the Department advised Kilkenny County Council that it did not object to the proposed refurbishments at Thomastown was not in a position to contribute financially to the work. A report on the home in 1952 makes it clear that no refurbishments had been undertaken and that the home remained without central heating and adequate lavatory and bathing facilities.

In February 1952, Department of Health inspector, Miss Alice Litster, inspected the nurseries at the home. She reported that 14 mothers and 45 children aged from new-born to 15 years were living there. One of the nurseries, 'a good room with polished floors' with four cots and two beds for adults, was occupied only by an eleven-year-old girl. A second nursery housed 20 'motherless children', with two adults sleeping in the room to attend to them at night. Infants who were accompanied by their mothers slept in the same bed with them at night. She described this nursery as a large room heated by an open fire. She observed that women sat in front of the open fire and that clothes were drying on a fire guard. She noted that the room was 'stuffy and squalid' and that the atmosphere was 'charged with odours associated with humanity cramped for space'. There was no lavatory accommodation in the nurseries and that chamber pots were available for the children. She also noted that 17 of the children were 'illegitimate' and the remaining three were extramarital children born to a woman who lived outside the institution caring for her other children. A third nursery was a dark room used at night to house 'motherless children'. A cupboard containing milk, bread, bottles and other articles was not in a clean condition. Older children were housed in an outside shelter heated by a turf burning stove. Most of the older children had been placed at nurse by their mothers and subsequently sent to the county home as their mothers had stopped paying maintenance for them. Miss Litster described other children as being either physically or mentally disabled.

The children's diet in 1952 was recorded by Miss Litster as follows:

| Breakfast | Porridge with milk; eggs about three days a week. Smaller children are started with a little yolk and increased until a whole egg can be taken. Bread and butter with milky tea. |

| Lunch | 'Goody' (bread, milk and sugar) |

| Dinner 1 p.m. | Soup, (made of meat with addition of vegetables, onions, carrots etc., as in season, thickened with barley or lentils, sometimes with addition of Bovril) given either separately or poured over potatoes and vegetables. Mashed potatoes and vegetables, a little minced meat. Pudding is given every day, generally cornflour, sometimes rice. Rhubarb and apples are given when available. Otherwise, except for very occasional orange, no fruit. Amount of milk given is regulated by appetite. Bread and milk is given in the afternoon. |

| Tea | Eggs may be given at this meal. Bread and butter and milky tea. |

Miss Litster noted that children living in the home 'appeared to be well-nourished, robust and on the whole in good health'. She drew attention to the 'large number' of children aged two years and over who were living there and recommended that they should be boarded out as soon as possible.

The unmarried mothers were housed in a dormitory at the top of the building. It was a long, narrow room with floorboards, clean, fresh and bright with ten windows. Each bed had a chair beside it and the room had a large communal wardrobe. The room had an electric light, but no heating. There was no sanitary accommodation attached to the dormitory and women were supplied with 'night pails'. Washing facilities for the women were provided on the ground floor. The dormitory could accommodate 24 women and was 'clean and comfortable'.

Miss Litster reported that the home's domestic work was undertaken by resident unmarried mothers. When the Department of Health asked the Kilkenny Board why unmarried mothers remained in Thomastown instead of being transferred to Sean Ross, the reply was that the women were required in the home to carry out work there. In July 1953, the Matron notified the Kilkenny Public Assistance authority that the number of unmarried mothers in the home had reduced to six and that she now had no-one to put to work in the institution. As a result. she had employed eight women to take up duties formerly undertaken by unmarried mothers.

In 1957, the institution was renamed St Columba's Hospital and it was decided to phase out the accommodation of single mothers. Subsequent Department of Health inspections recorded a steadily declining number of unmarried mothers or their children living in the establishment. In February 1965, there were none.

Former County Home main block, Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny, 2002. © Peter Higginbotham

In January 2021, Ireland's Mother and Baby Homes Commission of Investigation made its final report, which included an examination of the operation of the Thomastown County Home.

Between 1920 and 1972, there were almost 60,000 admissions to the home. These included 75 married maternity cases, 970 single expectant women and unmarried mothers, and 1,241 'illegitimate' children. In 1926, the county's Board of Health decided to exclude married women from using the maternity services at the home, directing them instead to the County Infirmary in Kilkenny. Admissions of single pregnant women to Thomastown home were highest in 1920-23 and fell by about half thereafter. This decline is probably associated with the opening of the mother and baby homes at Bessborough in 1922 and at Sean Ross in 1931. Admissions to Thomastown spiked during the Second World War and were particularly high between 1944 and 1946. This increase corresponded directly with the temporary closure of Bessborough to public patients and the temporary suspension of admissions to Sean Ross due to severe overcrowding. Admissions of single pregnant women to Thomastown declined steadily between 1946 and 1960.

The home's registers record 764 births there, all related to 'illegitimate' children. 77.8 per cent of the children were either born in the home or admitted there with their mother soon after birth; 11.7 per cent were older siblings accompanied by their mother, and 10.6 per cent were admitted unaccompanied. Many unaccompanied children were transferred from Bessborough and Sean Ross for boarding out. The subsequent destinations for 176 children born in the county home in the years 1931-61 were as follows: 101 (57 per cent) went home to live with their mother and/or grandparent; 55 (31 per cent) were boarded out; 14 (8 per cent) were sent to industrial schools; five (3 per cent) were sent to Sean Ross with their mother, and one child was informally adopted.

Of the 764 live births attributed to single women, 140 infants subsequently died. In most cases, the stated cause of death was 'inanition' — a lack of nourishment.

A groundsman at St Columba's told the Commission that he had been employed there since around 1986. He said that, in around 1990, the Matron of the institution, asked him and another employee to incinerate institutional records. He said that these records included burial registers relating to people who had died in the institution, including its time as a county home, and who were buried on the site. Shortly afterwards, groundsmen renovating the institutional graveyard, located in a field at the east of the hospital. He said that the graveyard, known locally as the 'Shankyard graveyard', had been neglected for some years and was in a state of disrepair. Several loads of topsoil were put down on the graves and that the site was levelled and grassed. The Commission visited the graveyard in 2019 and found the site to be well maintained. A single cross with the inscription 'Remembering those who died' marks the site as a former graveyard. The graveyard was in operation from 1854 to 1978. The Commission considered it likely that children who died in Thomastown county home were buried there.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- St Columba's Hospital, Cloghabrody, Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny, Ireland. Has: Combined Indoor Relief Registers (1919-72); Record of Maternity Hospital (1959-65); Record of Births (1919-65); Record of Deaths (1919-62). Return of Unmarried Mothers admitted to the County Home (1939-61); Half-yearly Return of Children in the County Home (1938-61).

- Kilkenny County Library, 6 John's Quay, Kilkenny, Co. Kilkenny. Workhouse-related holdings include: Guardians' minutes (1857-1926, with gaps).

Bibliography

- Nicolson, Jill Mother and Baby Homes: a survey of homes for unmarried mothers (1968, Allen & Unwin)

- Redmond, Paul Jude he Adoption Machine: The Dark History of Ireland's Mother and Baby Homes and the Inside Story of How Tuam 800 Became a Global Scandal

Links

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.