The Barnardo Story

Children with Disabilities

Thomas Barnardo always took a particular interest in the care of children with physical and mental disabilities, especially what were then usually referred to as "mentally deficient" or "feeble-minded". In the Girls' Village Home, such girls were given special training in skills such as embroidery. Barnardo also gained a personal interest in such children after the birth of his seventh child Marjorie who was born mentally handicapped. His general philosophy was that children with disabilities were better living amongst the non-disabled rather than being placed in segregated institutions, although there was a place for the latter in the provision of specialised facilities. In the 1890s, he promoted the use of boarding-out for children with mental disability. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the difficulties of providing for the mentally ill or intellectually impaired had forced a revision of his homes' open-ended admissions policy to exclude children "who are idiots or who have insane tendencies", with the category of epileptics being added a few years later.

Dr Barnardo with some of his 'cripple lads', c.1900. © Peter Higginbotham

At the time of his death, Barnardo had 8,000 children in his care, more than 1,300 of whom were handicapped. The organisation also had debts running to more than a quarter of a million pounds. Seeking ways of reducing expenditure, the Barnardo's governing Council raised concerns about the extra difficulty and expense of managing, educating and finding homes for afflicted children, particularly "feeble-minded" girls who, it was imagined, would become a growing long-term drain on the homes. As a result, between 1905 and 1925, the number of handicapped children in Barnardo's care fell from 16.25 percent to 5.0 per cent.

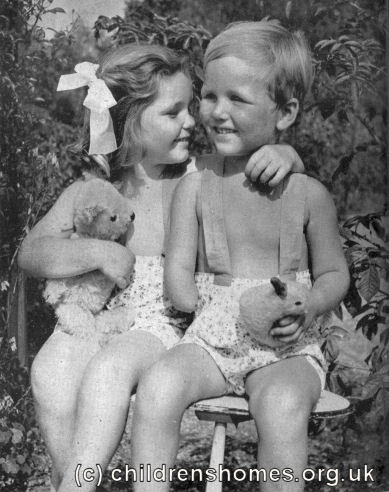

Child born with one hand now in Barnardo's care, 1930s. © Peter Higginbotham

Further action was taken in May 1928 with the opening of the Warlies home at Waltham Abbey for long-term residents of the Girls' Village Home who were classified as mentally defective and incapable of taking up normal life and work. However, the home was plagued by staffing difficulties and criticised by government inspectors for practices such as insisting on silence at mealtimes and sending the girls to bed as a means of punishment. By 1940 the project had been abandoned and the home used for other purposes.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.