Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor, London / Margate

The Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor was founded in 1792, the first institution of its type in England. A Mrs Creasey,the mother of a pupil at Thomas Braidwood's privately run Academy at Hackney, made the suggestion to John Townsend, a Dissenting minister of Bermondsey. He in turn gained support for the idea from the Rector of Bermondsey, Henry Cox Mason. The two of them began raising funds for the scheme, formed a small committee. In November 1792, the Asylum opened its doors in rented premises on Grange Road, Bermondsey, with just six children, thee boys and three girls. Four years later, however, there were twenty pupils, and a waiting list of fifty.

The Asylum's first superintendent was John Watson, a nephew of Thomas Braidwood and previously one of his assistants at the Hackney Academy. The arrangement that was decided for the appointment of the superintendent was that it would be unpaid but that post-holder would make a living from the profit he made on his contracts from school supplies and from any private pupils he might take. This was to turn out to the Asylums disadvantage, as the superintendent invariably focused rather more of his attentions on his own fee-paying pupils than on those admitted free. By 1795, an assistant, Robert Nicholas, was appointed to teach the poor children. The Asylum used a combined method of instruction, which incorporated both the 'oral' system of vocalization and lip-reading, and the 'manual' system, which was based on signs and finger-spelling.

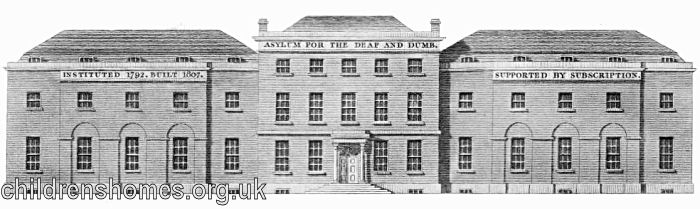

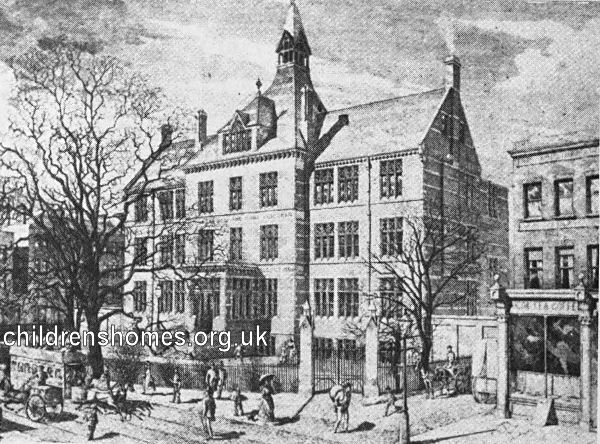

The Asylum continued to grow and in 1809 moved into large, purpose-built premises on the Old Kent Road. By that date there were eighty children, trade training had been introduced as the waiting lust was longer than ever. The Asylum site is shown on the 1875 map below, the adjacent Townsend and Mason Streets having been named after the institution's founders.

Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor site, Old Kent Road, c.1875.

Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor, Old Kent Road, London, 1822.

Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor, Old Kent Road, London

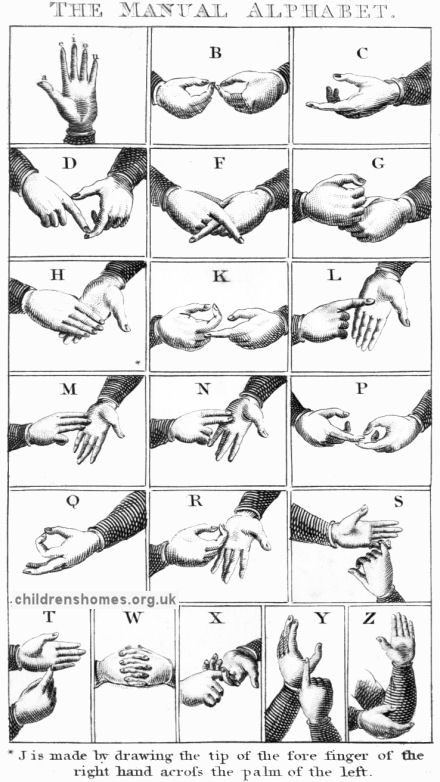

Thomas Braidwood had always sworn his assistants to secrecy about the techniques he had devised. After Thomas's death in 1806, John Watson felt himself free to reveal these methods, which he did in Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, published in 1809. He started with getting his pupils to articulate basic speech sounds, combining speech elements into into symbols then into words. Afterwards, the children would learn to read and write. Watson employed a manual alphabet, with which they could spell out words using hand gestures.

John Watson's Manual Alphabet system, 1809.

Joseph Watson remained in post until his death in 1829. He was succeeded by his son, Thomas James Watson, who had assisted his father and, for a time, had been headmaster of the Glasgow Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. When Thomas James died in 1857, he was succeeded by his son, a great-great-nephew of Thomas Braidwood, the Rev. James H. Watson.

In 1862, the charity was incorporated by an Act of Parliament which provided for the better protection of its property and for the more efficient carrying out of its aims. In the same year, it took over St John's College in Margate, which was converted to provide temporary accommodation for an additional sixty children.

In 1867, it was reported that the Asylum contained a total of 350 children — 207 boys and 143 girls.

From around 1868, the charity was sometimes referred to as the Asylum for the Support and Education of Indigent Deaf and Dumb Children, often shortened to the Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb.

on 11 January 1868, the Old Kent Road establishment was licensed as a Certified School, allowing it to receive children boarded out from workhouses by the Poor Law authorities. It continued to hold this status until 20 June 1884.

On 19 July 1875, a large newly-erected building on Victoria Road, Margate, was formally opened by the Prince and Princess of Wales, although the planned festivities were curtailed by the day's incessant heavy rain. The building, which could house 150 children was designed by Messrs. Drewe & Bower of Margate, and cost £16,000. Its schoolroom, measuring 96 feet by 25 feet was common to both sexes, and had the boys' dormitories above it. The girls' work-room, 40 feet by 25 feet, had the girls' dormitories over it. The dining-hall was described as a spacious apartment with an open timber roof supported on carved angels as corbels. Fire-proof corridors 6 feet wide connected the various rooms and staircases, three in number. One peculiarity of the design was said to be the arrangement of teachers' rooms, which was, in effect, never to leave the children without supervision. The Margate branch was used to educate the older pupils, while the younger pupils resided in London.

Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor site, Margate, c.1905.

Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor, Margate, from the north-west, c.1908.

James Watson resigned as headmaster in 1878, an event which ended the Asylum's connection with the Braidwood family ended. Richard Elliot was then appointed head of both branches of the institution.

In 1883, as part of an overhaul of Asylum's accommodation, the younger pupils moved from London to temporary accommodation in Ramsgate, which was referred to as the Asylum's 'oral branch', also known as the St Lawrence Asylum. At the end of 1886, the children at Ramsgate were transferred to the Margate branch where a new wing increased its accommodation At the same time, the Old Kent Road premises were rebuilt, occupying only part of the existing site. The new building accommodated just sixty children and received new admissions, to prepare them for the oral system of tuition at Margate, to where they were transferred after about twelve months.

Asylum for the Support and Education of the Deaf and Dumb Children of the Poor, Old Kent Road, after rebuilding in 1885.

In September 1886, a reporter from The Globe newspaper visited the Ramsgate branch to learn about its 'pure oral' teaching method. He also went on to call at the Margate establishment.

I was received by Mr. Elliott, the head-master of the institution. From this gentleman, who, as Vice-President of the Education Congress of 1885, delivered some remarkable papers on the teaching of deaf and dumb, I gather much interesting information, and then proceed under his guidance to visit the pupils in class. In order to be efficacious the oral system must be learned by children at an early age, it being all but impossible for adults to acquire it with any great amount of success. The pupils adopted by the Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Children must be between the ages of seven and ten, and the course of tuition endures for about five years.

Following the head-master across a passage, and passing two or three little boys on their way to the schoolroom, one of whom, much to my astonishment, stands aside and distinctly enunciates “Good afternoon, sir,” we enter a commodious class-room, in which the junior pupils are being conducted over the pons asinorum of lip reading and articulation. The children being absolutely deaf and dumb, are not only incapable of speaking, but also of hearing any sound which they may themselves enunciate. The method employed in their tuition is therefore the reverse of that used with ordinary children, inasmuch as they are not taught to imitate sounds, but to perform actions by which they unconsciously produce sound. The teacher, standing before his class, which, by the way, consists of only eight children, it being impossible for one person teach a large number simultaneously, enunciates a letter, consonant or vowel, very distinctly. The children watch the speaker's lips and try to imitate their movement. The letters are spoken phonetically, and not alphabetically, thus the letter “f,” which was being taught at the time of my visit, is not named, but sounded, the operation being performed by bringing the upper teeth in contact with the lower lip and blowing slightly. The children imitate the action perfectly, but the majority do not blow, and, as consequence, produce no sound. The teacher is quite prepared tor this, and, taking the hand of one of the pupils, places it in front of his lips while he enunciates “f.” The learner feels his hand blown upon, and the teacher presenting his own hand to the pupil's lips, the idea enters the young mind, and results in a perfect “f.” So soon this as this sound has been mastered the teacher writes “f” on the black-board, and the children rapidly understand that it is the symbol calling on them to go through the above performance. In the same way the letter “g” is taught pronouncing it with the lips, and pressing the pupil's fingers against the throat muscles of the teacher, which vibrate when gutturals are spoken. By placing the child's hand on his own throat, he is made to understand that he is to make a similar vibration, which he does, thereby enunciating the letter in excellent form. So soon as a few letters are mastered, together with their accompanying symbols on the black-board, the children are made to sound them in words. A little girl of ten is called up to the board, and “m” is written and pronounced. The letter “a” presents some difficulty. She knows the sign, and interprets it by opening the lips and emitting a guttural sound like “oi.” The teacher soon sees the cause. The child is pressing its tongue against the roof of the mouth instead of against the lower teeth, and the right sound is taught by pressing a small piece of ivory in the child's mouth and depressing the tongue while she sounds a perfect “a.” The letter “t” next written is at once pronounced, and the whole word “mat” read off with ease. The spelling follows as a matter of course, inasmuch as the whole teaching being phonetic the children simply sound the letters succession. Words having dormant or redundant letters are spelt by sounds, as for instance, “poosh,” which the children at once decypher “push.” The proceeding is so wonderfully simple and so exceedingly interesting that I would fain have staid a whole day with these mute conversationalists. There are, however, nine classes to be seen, each of a different grade. and Mr. Elliott being desirous that I should also see the advanced scholars, I consent, not without regret, to pass on to the next class, in which, besides articulation and lip-reading language, the expression of ideas, writing, and arithmetic are taught with equal success.

The children in this class have mastered all their letters, and also a number of single words. To convey ideas to them, it is by no means necessary to converse audibly. All that is wanted is to go through the action of pronunciation clearly and distinctly, and, by the attitude and motion of the lips and facial muscles, they gather the ideas they are accustomed to connect with the movements they see before them. Thus they are told, the speaker moving his lips, but making no sound, “Go to the window,” and immediately a number of them hold out their hands for permission to obey the command. “Sit on the chair,” “Pull her hair,” “Cross your hands,“ and other simple commands are given and obeyed without any hesitation. The difficulties attending this system can be gleaned from one example. The children being taught words and their signification, are liable to fail in their distinction of tense. Thus, having written on the black board, “What can fly?” the child selected to write the reply inscribes, “Bird is fly,” a statement in which the whole class agrees. In the next class, colloquial conversation, actions, and the description of pictures are taught, in addition to the usual lip-reading and articulation. These children are considerably more advanced than the others, several being exceptionally acute in their perception. One little lassie of 12, whose name is Ruth, especially distinguished herself in her conversation, writing words on the black board which she heard only for the first time. Any defect in pronunciation is at once corrected by the teacher, as. for instance, when little Ruth could not pronounce “understand,” which she rendered “uderstu.” The “n” was made plain by placing the child's hand on the bridge of the teacher's nose, to render the vibration plain, and the “d” exhibited in the same way in the throat. The child immediately understood and pronounced the word correctly. In the other classes the same thing is to be seen a little more advanced in each remove, but being anxious to pass some time with the more advanced pupils, I skipped the intermediate divisions, and was conducted to the first class where are those children, varying in age from 12 to 15, who are shortly to leave the school and enter the world. The curriculum here includes Scripture history, letter-writing, mental arithmetic, grammar, &c., and in geography they are particularly good. The lip reading powers of these advanced students is wonderful. Mutter any ordinary sentence one will, and they can immediately repeat it, define it, write it on the board, and are ready to obey the order if told to do so. In order to understand the speaker it is only necessary for them to have a full view of his face, and the rapidity with which they comprehend words which they cannot hear is little short miraculous. Among the particularly bright specimens I interviewed are Harry Challen, a lad of 13, brother to little Ruth; Clara Reynolds, probably the best articulator in the school; Jane Barrott, a particularly intelligent lassie of 13; and Joseph Britten, a famous writer, in class I. It is remarkable how exceedingly well all these children write. Many of their exercises look like copperplate, and they form their letters with a free and easy hand that should open any counting-house to them with alacrity. As matter of fact, but few take to book-keeping as a means of livelihood. Among other benefits conferred by the asylum is the payment of apprenticeship fees for those pupils who are deserving and poor, and no fewer than 1,848 boys and girls have been started in life since 1811, when the practice began. The institution itself was founded in 1792. It possesses, therefore, an independent interest in its antiquity, and, to point to the benefits conferred, it is only necessary to state that 4,760 children have passed through its schools. The Ramsgate building is only a temporary establishment. At Christmas my little acquaintances will be moved to the new wing of the Margate Asylum, whence I directed my steps after having been shown over the one at St. Lawrence. The new asylum is a gigantic affair, comprising a magnificent pile of buildings, standing in nine acres of picturesque grounds. It was not the building, however, but the children that I had come to see, and of these there are many more here than at St. Lawrence. At the latter there are at present 90 children; at Margate there are 220. All of these are totally deaf and dumb. About two-thirds are boys, and 70 per cent. are congenital cases.

To detail the interesting sights I saw at the Margate Asylum is impossible. To describe the mode of communication existing between those children who have not been taught the Oral system would be foreign to the purport of this article. I cannot, however, refrain from alluding to the wonderful facility obtained by practice in speaking dactylologically. To watch Miss Howard, the excellent matron, or Miss Edwards, her assistant, instruct or converse with the children by aid of the finger alphabet seems marvellous to the beholder, while to note the sign language spoken between the children themselves when out of school hours, for it is strictly forbidden to “sign” in school time, is even more astonishing. To quote Mr. Elliott, who, with his 28 years' experience at this one institution, speaks with weighty authority, “We don't teach all children signs, they teach us,” and it doubtless is so, since two strange children who are brought together within the asylum walls will be conversing freely with one another by signs within half an hour of their arrival. It was my fortune to see this actually occur, as it was also to see little Agnes Whiteman (who with exquisite humour confided to me that she was really a white woman), the acknowledged pet of the school, speak the language. A little child named Maria Lugsden is also a wonderful dactylologist, an art in which she is even excelled by William Currie, a capital lad of about 13. I cannot detail the wonderful game of chess played by two of the lads, but am assured that but few good players can beat them at the game. In conclusion, I can truthfully aver that it is impossible to spend a more interesting or instructive day than by going to the Deaf and Dumb Asylums, and chatting with the inmates at either Margate or Ramsgate, and I can assure those of a nervous temperament that there is nothing unpleasant or disagreeable to be seen either establishment.

In 1890, the admission process for the Asylum was stated as follows:

Admission: By election of subscribers, presentation, or payment. Donors of £5. 5s. and subscribers of 10s. 6d. have one vote for each vacancy. Donors of £210 have 40 votes for each vacancy, or can keep one child always on the foundation. Children admitted by payment: £30 per annum. Forms of application obtained from the Secretary must be filled up and returned by the third Monday in April or October. Candidate must furnish certificate of being deaf and dumb, and, if elected, security for removal in case of sickness or death, or when required. Candidates must be between 7 and 10 years of age, unless specially exempted; be vaccinated, and not imbecile or deficient in intellect. Children from the workhouse are taken on payment. Inmates are taught reading, writing, dictation, arithmetic, history, geography, and drawing. The girls are taught needlework and household work. Every child capable of being so taught is educated under the 'Pure Oral' System by teachers specially appointed for that purpose. On leaving, inmates may apply to be apprenticed to suitable employers.

Oral class at London Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Children, Margate branch, 1892. © Peter Higginbotham

Girls' gymnasium at London Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Children, Margate branch, 1892. © Peter Higginbotham

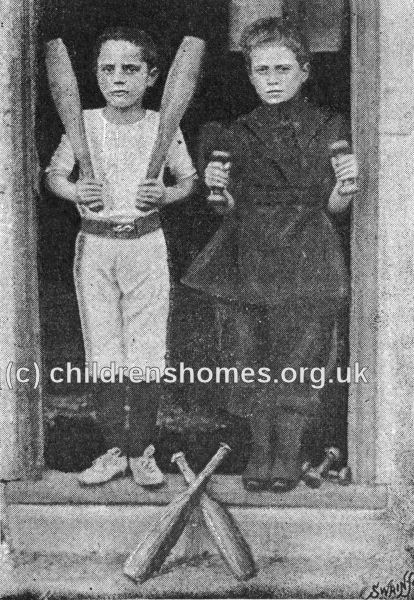

Evan Williams (age 9) and Rhoda Pippeck (10( with clubs at London Asylum for Deaf and Dumb Children, Margate, 1892. © Peter Higginbotham

In 1901, King Edward VII granted the Asylum the privilege of using the prefix 'Royal' in its name.

In 1902, the charity decided to concentrate all its activities at Margate and the Old Kent Road site was sold to the London School Board. The building was enlarged and re-opened as a school for physically handicapped children on the ground floor and a school for deaf children on the second floor. The School Board was taken over by the London County Council in 1904. The school closed in 1968 and transferred to new premises at Grove House in Elmcourt Road, Norwood, which closed in 1999.

LCC School for Physically Defective and Deaf Children site, c.1914.

In 1908, the Asylum was renamed the Royal School for Deaf and Dumb Children. The word 'Dumb' was later dropped.

Most of the Victorian building was demolished in 1974 and replaced by modern buildings. A small section was used to house a museum for the deaf.

In 2008, a new body, the John Townsend Trust, was formed to run the school. The School closed its doors in December 2015, with the Trust going into liquidation and reports of the abuse of students in part of the institution being made by the Care Quality Commission.

In 2021, there were plans to demolish the existing buildings and erect a new school on the site.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Kent History and Library Centre, James Whatman Way, Maidstone, Kent ME14 1LQ Holdings include student files, minutes, accounts, scrapbooks, photographs and plans.

Census

- 1881 Census — Old Kent Road

- 1881 Census — Margate

Bibliography

- Beaver, Patrick, A Tower of Strength: Two Hundred Years of the Royal School for Deaf Children, Margate. (Book Guild, 1992).

- Higginbotham, Peter Children's Homes: A History of Institutional Care for Britain's Young (2017, Pen & Sword)

- Pritchard, D.G., Education and the Handicapped 1760-1960 (1963, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Watson, J, Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb (1809)

- Watson, Thomas J., A History of Deaf Education in Scotland 1760-1939 (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, 1949)

Links

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.