Wellington Farm School for Boys, Penicuik, Midlothian, Scotland

In March 1859, at a meeting of subscribers and friends of the Edinburgh Association for Promoting the Reformation of Juvenile Male Offenders, it was agreed to establish an institution for the purpose. A suitable location was subsequently found near Leadburn, about two miles to the south of Penicuik, comprising the old Wellington Inn and several adjacent fields. The whole site formed a farm of about ninety acres, which was initially leased for a period of nineteen years. The inn building was altered and adapted under the direction of Mr F.T. Pilkington, architect, to provided a schoolroom, a dormitory, a workshop, a bath, a washing house, houses for the superintendent and grieve, and a five-stalled stable. The premises were formally certified to operate as a Reformatory on 24 December 1859. Mr John Craster, previously head of the Reformatory at Inverness, was appointed superintendent.

The first boys sentenced to detention in the school were two received on 18 February 1860 and three more on the 27th, on which day it was decided to open the school formally by inviting the ministers and others in the neighbourhood to a meeting in the schoolroom.

An inspection in November 1862 recorded 76 boys at the school, more than could be properly accommodated in the sleeping quarters. Of the ninety acres belonging to the school farm, nearly seventy had been brought into cultivation. The land was poor and exposed, and it was likely to take some time before it would show a profit. 'Very fair' crops of oats, barley, potatoes and turnips had been produced, however. The farm stock comprised five cows and three horses. The indoor employments consisted of tailoring, shoemaking, and carpentering, the latter including the use of a turning lathe.

In 1863, extensions to the buildings included a day-room, and workroom, cow-house, barn, and a larger stable. The boys made a substantial contribution to the work and also helped to build some cottages which would provide a residence for the schoolmaster or other assistants. After further additions over the following year, the school buildings formed three sides of a square, with the schoolroom, dormitories, and lavatory on one side, the work and day rooms, office, dairy, etc. on the other, and the superintendent's house and boys' dining room occupying the centre. The farm buildings and yard had also been completed and a threshing machine installed. About thirty boys were now sleeping in the farm cottages in the charge of the schoolmaster and one or two of the industrial assistants who resided there. A further cottage was subsequently erected a few hundred yards from the main buildings to house the schoolmaster, with accommodation for twenty boys attached.

The layout of the school site is shown on the 1895 map below.

Wellington Farm School for Boys site, Penicuik, c.1895.

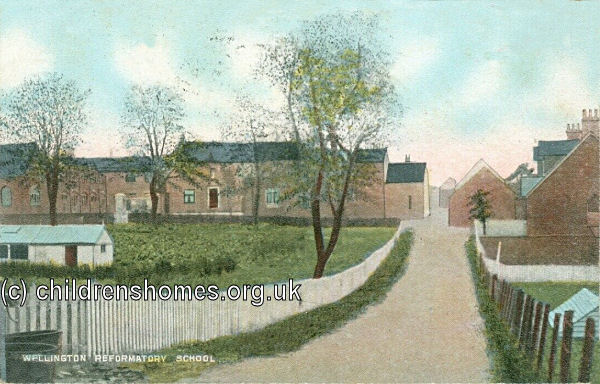

Wellington Farm School for Boys from the west, Penicuik, c.1909.

In 1869, an adjoining farm of 160 acres was taken in hand by the school in order to provide employment for the growing number of inmates, now averaging over 100. The staff now consisted of Mr John Craster, superintendent; Mrs Jane Craster, matron; Mr Malcolm, schoolmaster; master tailor, shoemaker, carpenter, farm bailiff, and five assistants.

The 1871 inspection noted that the boys generally behaved well but had been rather restless and troublesome since a break-out during Mr Craster's absence when a large number of them had left the school and amused themselves in a day's ramble over the hills.

Although cultivation of the farmland occupied many of the boys, the indoor workshops were very productive. The shoemaking shop was notable in being equipped will the latest American machinery, allowing it to undertake large contracts. By 1873, a depot had been established in Edinburgh for the sale of the articles being produced and was said to be well supported. In addition to carpentry, shoe-making and tailoring, some of the boys were engaged in the manufacture of peat fuel from the moss, and in rag-cutting for the paper mills at Penicuik — the latter occupation being the subject of some objection by the school's inspector. The boys were encouraged in their exertions by fair money rewards for work done and, within certain constraints, could dispose of their earnings as they thought fit.

In the spring of 1879, there were 16 cases of smallpox at the school. The first four boys attacked were all engaged in the rag-picking department. The worst cases were sent to the Edinburgh Fever Hospital, and were returned to the school cured. The rag-picking was at once discontinued, all the rags on the premises removed, and every part of the premises disinfected.

Further improvements were made to the premises in 1880. The large building formerly used for rag-picking was turned into an additional shoemaker's shop. The old carpenter's shop was been turned into a large and airy dormitory, which was to be used as an infirmary if required. A large playground was been enclosed, and a new boiler house built. There was now a drum and fife band.

By 1881, Mr John Craster Junior had become the school's book-keeper. In 1886 he had become assistant superintendent.

In 1888, about 200 acres of the farm's rented land were given up. The remainder, about 80 acres of farm land and 30 acres of peat moss, were all now owned by the school. About 14,000 pairs of boots and shoes were produced during the year. Steam was now used for cooking and heating.

In his 1896 report, the inspector commented that the boys were not as alert and bright in appearance as could be desired. His suggested remedy was the provision of a gymnasium and swimming bath, and an extra subject or two in school. A better tailor's shop was urgently needed. On the positive side, it was noted that the boys were allowed freely to read in the dormitories, to carry pocket money, and were not prohibited from having knives. Although there was no mark system, work and good conduct were encouraged by a system of wages (£10 in 1895) and good prizes (e.g. 6 silver watches during the year). Three or four boys were emigrated every year from the school with successful results.

In 1899, a new water supply was provided by means of a pump powered by a windmill. A tank was erected capable of holding 7,000 gallons. That year's inspection report warned the school's managers not to rest on their laurels as regards maintaining the income necessary to keep up with modern improvements in education and industrial and physical training. The now widespread mechanization of the shoemaking and tailoring industries, and falls in the prices for agricultural produce were inevitably leading to a drop in profits from those sources. In addition, generosity of the charitable public was less drawn to reformatories than to industrial schools and orphanages. The inspector suggested that appeals be made to the local authorities from which boys were committed to grant them a weekly sum of, say, 2s. 6d. per week. Such arrangements had been implemented in the south at institutions such as the Redhill Farm School.

In July 1890, the death occurred of John Craster, aged 66, who had been superintendent of the school since its opening in 1859. He was succeeded by his son John.

In an effort to improve the institution's physical training and recreation facilities, some apparatus for physical development was fitted up in the schoolroom in 1901. Improvements were also made to the school's playfield and matches organised against outside teams. A '9-pounder' was purchased in order to teach the boys gun-drill. The industrial training in tailoring and shoe-making now included more theoretical aspects of the subjects, such as the origin of the materials used, prices, taking measurements and drafting garments and boots. Drawing was taught in the tailoring department.

In March 1903, Miss Craster was appointed as assistant matron. Her mother, Jane Craster, matron of the school since its opening in 1859, died on 25 July 1904 at the age of 79. She was succeeded as matron by her daughter-in-law, Catherine Craster, the wife of the superintendent.

A running track had now been set up around the playfield and free gymnastics were carried out under the instruction of the assistant superintendent. A museum was instituted, one of its most prominent features being a large collection of birds' eggs.

In 1907, parallel bars and vaulting horses had been purchased and some simple exercises taught on each. The whole school were now instructed in free gymnastics, some also performing exercises with dumb-bells. A debating society was formed during the winter, giving an impetus to the school library and reading club. Ambulance classes, concerts and lantern lectures were also been held in the winter months. The boys' clothing was improved, with heavier flannels worn in winter. Jerseys were introduced, together with clogs for the farm boys. A course of 14 lectures was given by a lecturer from the East of Scotland College of Agriculture.

In 1911, there were 100 boys at the school, with 10 out on licence. A manual instruction workroom had been set up for the teaching of woodwork and metalwork. Rifle shooting had now been added to the boys' activities. The staff now comprised: superintendent and matron, Mr and Mrs Craster; assistant superintendent, Mr T. Fleming; head schoolmaster, Mr A. Mclsaac; assistant schoolmaster, Mr J.E. Peart; three shoemakers, tailor, engineer and manual instructor, farm grieve and assistant, janitor, night watchman, visiting bandmaster, laundress, and dairy maid. The school's dentist was Mr R. Pringle.

In 1933, Wellington became an Approved School, one of the new institutions introduced by the Children and Young Persons (Scotland) Act to replace the existing system of Reformatories and Industrial Schools. It now accommodated up to 80 Senior Boys, aged 14 to 17 years at their date of admission. Though now officially known as Wellington School, the institution long retained its popular nickname of 'Wellie Farm'. In 1943, the school was described as having a farm and garden and a large shoemaking department, with carpentry and tailoring also taught. There was also a band. The headmaster at that date was Mr J. Innes.

The 1968 Social Work (Scotland) Act aimed to bring Approved Schools in Scotland under the control of local authority social work departments. As a result of a title in a list drawn up by the Scottish Education Department, the School was redesignated as a 'List D' School and was tun by Edinburgh City Council. In the 1970s, the school moved into new premises at the opposite side of the main road. It finally closed in 2014.

Virtually all the original school buildings have been demolished.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- None identfied at present — any information welcome.

Census

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter Children's Homes: A History of Institutional Care for Britain s Young (2017, Pen & Sword)

Links

- None identified at present.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.