The Waifs and Strays Story

Expansion

In February 1882, soon after the original Dulwich home opened, a receiving home for boys was established at Clapton. A third home, for girls, was opened in late 1882 at Old Quebec Street, Marylebone.

The response to the opening of these first homes soon made it apparent that, despite the provision already being made by other charities and by the Poor Law authorities, the problem of destitute and homeless children on the streets of the nation's towns and cities was enormous. In April, 1883, the Society decided to establish boys' and girls' Receiving Homes in every diocese. Plans were already forming for a Receiving Home in Canada. All children's homes with Church affiliations were contacted as potential recipients of the children being received. Efforts were also being made, particularly in rural areas to find foster parents. By the end of the year, however, it had become apparent that in order to meet the demand it had opened up, the Society would itself need to operate long-term residential homes. Reflecting this, the Society changed its name from 'The Church of England Central Home for Waifs and Strays' to 'The Church of England Central Society for Providing Homes for Waifs and Strays' — usually shortened to just 'The Waifs and Strays Society'.

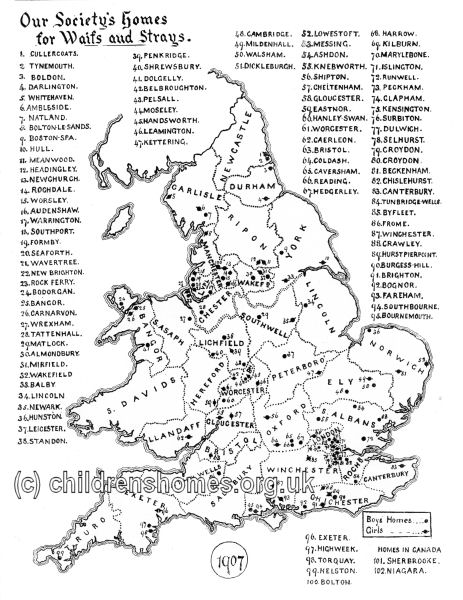

The homes expanded rapidly. In 1882, the Society had 34 children in its care; by 1902, this had risen to 3,071. Likewise, the number of its homes over the same period rose from two to ninety.

Map of Waifs and Strays Home locations, 1907.

From the outset though, the Society used four different channels to find homes for the children it received. These were: passing children on to other organisations; the use of fostering, also known as 'boarding-out'; assisted emigration to Canada; and placement in the Society's own homes. These channels varied in what children they could absorb, however. The Society restricted placements with foster parents to children under the age of seven. Emigration was limited by the Canadian authorities to children over twelve. And the total amount of accommodation provided by other organisations was relatively static. There was a particular need to find homes for children aged ten or over.

Pressure for places in the Society's homes also came from the workhouse authorities who, since 1862, had been empowered to board out children in establishments run by other bodies and that had been approved for the purpose. The Society's ideal of 'saving' children from an institutional upbringing in the workhouse meant that it felt obliged to rise to this challenge.

As the Society became established and well-known, properties were increasingly donated to it. In some cases, such as the Stroud Green Home for Girls, these were existing children's homes which were in danger of closing for some reason. Perhaps their finances were shaky, or their founders wished to retire. In other cases, the properties were given to the Society which could be turned into a home as happened with the Hatton Home for Boys in Wellingborough.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.